Why ACE Inhibitors Are Contraindicated in Renal Artery Stenosis

ACE Inhibitor Safety Checker

Risk Assessment Tool

Enter values and click "Check Risk Level" to see your risk assessment.

When you're on high blood pressure medication, you expect it to help-not hurt. But for some people, a common drug class called ACE inhibitors can cause sudden, serious kidney damage. This isn’t a rare side effect. It’s a well-known, life-threatening contraindication tied to a specific condition: renal artery stenosis.

What Happens When Your Kidney Arteries Narrow

Your kidneys don’t just filter waste. They also help regulate blood pressure. Each kidney gets its blood supply from a renal artery. When one or both of these arteries narrow-usually from plaque buildup (atherosclerosis) or fibromuscular dysplasia-that’s renal artery stenosis.Here’s the problem: less blood flow means your kidney thinks your whole body is low on blood pressure. So it releases renin, which triggers a chain reaction. Renin leads to angiotensin I, which gets converted to angiotensin II-the body’s most powerful natural vasoconstrictor.

Angiotensin II does two key things in a narrowed kidney:

- It squeezes the tiny efferent arteriole leaving the glomerulus (the filtering unit).

- This keeps pressure high inside the glomerulus, so filtration doesn’t crash even when blood flow is low.

Think of it like pinching a garden hose at the end. The water pressure builds up upstream, so the spray still works-even if the water coming in is weak. That’s how your kidney keeps working with reduced blood flow. Angiotensin II is the pinch.

How ACE Inhibitors Break This System

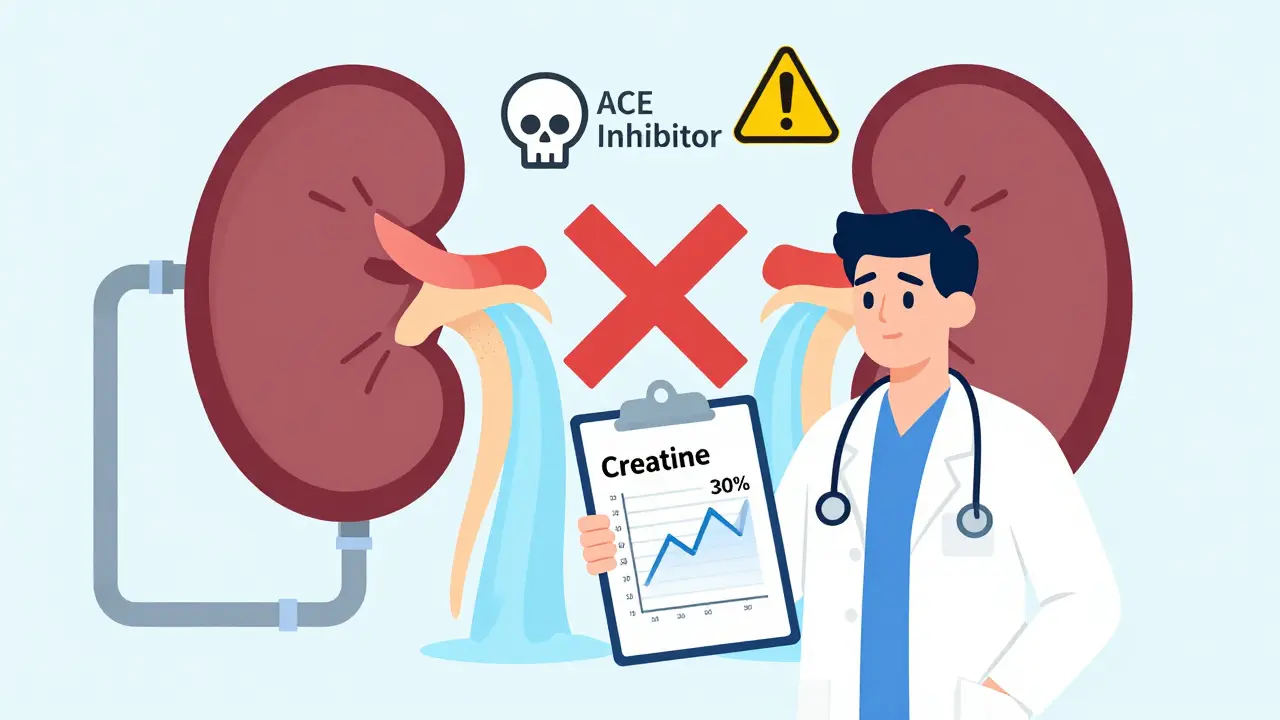

ACE inhibitors block the enzyme that turns angiotensin I into angiotensin II. That’s great for most people-it lowers blood pressure, reduces heart strain, protects kidneys in diabetes. But in someone with bilateral renal artery stenosis (both kidneys narrowed) or a single functioning kidney with stenosis, this is like suddenly releasing the pinch on the garden hose.Without angiotensin II, the efferent arteriole relaxes. Glomerular pressure drops by 25-30%. Filtration slows. Creatinine rises. Kidney function crashes.

This isn’t a mild fluctuation. Studies show that within 7-10 days of starting an ACE inhibitor, up to 20% of people with undiagnosed bilateral renal artery stenosis will see their serum creatinine jump more than 30%. That’s acute kidney injury. In some cases, it’s permanent.

One landmark 1984 study in the New England Journal of Medicine found 12 out of 15 patients with bilateral stenosis developed acute renal failure after taking captopril. That’s why the warning was added to labels-and why it’s still there today.

The Difference Between One Kidney and Two

Not all renal artery stenosis is the same. If only one kidney is affected and the other is healthy, your body can compensate. The good kidney picks up the slack. In this case, ACE inhibitors can often be used safely-with close monitoring.But if both kidneys are narrowed, or if you only have one kidney (due to transplant, removal, or congenital absence), there’s no backup. The angiotensin II system is your only lifeline. Block it, and your kidneys can’t maintain filtration.

That’s why guidelines are crystal clear: ACE inhibitors are contraindicated in bilateral renal artery stenosis or stenosis in a solitary kidney. The FDA, American Heart Association, and KDIGO all list this as a hard no.

What About ARBs? Are They Safer?

Some patients and even some doctors think switching from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB (like losartan or valsartan) solves the problem. It doesn’t.ARBs block angiotensin II at the receptor level. They don’t stop its production-but they stop it from working. The result? Same drop in glomerular pressure. Same risk of acute kidney injury.

The 2019 KDIGO guidelines explicitly state that ARBs carry the same contraindication as ACE inhibitors in renal artery stenosis. Using an ARB instead isn’t a workaround. It’s just a different path to the same danger.

Who Should Be Screened Before Starting ACE Inhibitors?

You don’t need to test everyone. But if you have any of these red flags, your doctor should check for renal artery stenosis before prescribing an ACE inhibitor:- Sudden, unexplained rise in creatinine or worsening kidney function

- Accelerated or resistant hypertension (blood pressure that won’t budge despite multiple drugs)

- An abdominal bruit-a whooshing sound heard with a stethoscope over the belly

- History of atherosclerosis (heart attack, stroke, peripheral artery disease)

- Unexplained kidney shrinkage on imaging

Studies show 6.8% of hypertensive patients with kidney problems have significant renal artery stenosis. That’s not rare. It’s common enough to warrant screening.

The go-to test is a renal artery duplex ultrasound. It’s noninvasive, widely available, and has 86% sensitivity and 92% specificity for detecting hemodynamically significant narrowing. If it’s positive, a CT or MR angiogram may follow for confirmation.

What If You’re Already on an ACE Inhibitor?

If you’re already taking an ACE inhibitor and your doctor hasn’t checked for renal artery stenosis, don’t panic. But do ask:- Have you had your kidney function checked since starting the drug?

- Was your creatinine measured before and then again 10 days later?

- Do you have any risk factors like high cholesterol, smoking, or prior vascular disease?

NICE guidelines recommend checking serum creatinine and potassium before starting, then again at 7-14 days after initiation or after any dose increase. If creatinine rises more than 30%, stop the drug and investigate for renal artery stenosis.

Here’s the good news: if caught early, the kidney damage is usually reversible. Most patients recover normal kidney function within days to weeks after stopping the ACE inhibitor. But if the low blood flow lasts more than 72 hours, permanent scarring can occur.

Why Do Doctors Still Prescribe Them Anyway?

Despite decades of clear warnings, a 2020 study found that over 22% of patients with known bilateral renal artery stenosis were still being prescribed ACE inhibitors in primary care clinics across the U.S.Why? Three reasons:

- Many doctors don’t routinely screen for renal artery stenosis-it’s not part of every hypertension workup.

- Patients often don’t have symptoms. The stenosis is silent until the drug is started.

- ACE inhibitors are so widely used for heart failure and diabetic kidney disease that the contraindication gets overlooked.

It’s not negligence. It’s a gap in systems. A patient walks in with high blood pressure. They’re prescribed lisinopril. Two weeks later, they’re back with nausea and fatigue. Creatinine is up. They’re rushed to the ER. The root cause? A blocked kidney artery no one tested for.

What Are the Alternatives?

If you have bilateral renal artery stenosis or stenosis in a single kidney, you need blood pressure control-but safely. Here are the options:- Calcium channel blockers (like amlodipine): First-line choice. They dilate arteries without affecting kidney filtration pressure.

- Diuretics (like chlorthalidone): Help reduce fluid overload and lower pressure without impacting renal hemodynamics.

- Beta-blockers (like metoprolol): Useful if you also have heart disease or arrhythmias.

- Renal artery intervention: In some cases, stenting the narrowed artery may be considered-but studies like ASTRAL show it doesn’t improve kidney outcomes over medical therapy alone in most patients.

The goal isn’t to treat the stenosis. It’s to control blood pressure without harming the kidneys. That’s why calcium channel blockers are often the safest bet.

The Bottom Line

ACE inhibitors are powerful, life-saving drugs-for most people. But for those with bilateral renal artery stenosis or a single kidney with narrowing, they’re dangerous. This isn’t a theoretical risk. It’s a documented, preventable cause of acute kidney failure.If you’re on an ACE inhibitor and have any of the risk factors listed above, talk to your doctor. Ask if you’ve been screened. Ask for your creatinine values before and after starting the drug. Don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s commonly prescribed.

And if you’re a doctor: don’t skip the basic checks. A simple blood test and a quick history can prevent a hospital stay-or worse.

Medications aren’t one-size-fits-all. Sometimes, the safest choice isn’t the most popular one.

Pat Dean

January 17, 2026 AT 22:11This is why I don't trust Big Pharma's 'one-size-fits-all' bullshit. They push these drugs like candy, then act shocked when people end up on dialysis. ACE inhibitors? More like ACE-killers for people with hidden stenosis. Someone should sue the damn manufacturers.

Jay Clarke

January 18, 2026 AT 22:57Bro, I had my creatinine jump 40% after starting lisinopril. Docs just said 'it's normal' and doubled the dose. Turns out I had bilateral stenosis-silent as hell until the drug nearly killed my kidneys. Now I'm on amlodipine and feel like a new person. Why isn't this common knowledge?!

Selina Warren

January 20, 2026 AT 19:24Let me tell you something real-your kidneys don’t care about your blood pressure numbers. They care about blood flow. And when you block angiotensin II in a stenotic kidney, you’re not lowering BP-you’re turning off the life support. This isn’t pharmacology. It’s survival. If your doctor doesn’t get this, find a new one. Your kidneys won’t wait for a second opinion.

Robert Davis

January 21, 2026 AT 10:07Interesting. I wonder if this is why my uncle’s kidney function never recovered after his heart failure med change. He was on lisinopril for years. Never had a bruit, never had symptoms. Just… slowly declined. Now he’s on transplant list. Was it the drug? Or just aging? Hard to say. But I’m not taking any ACE inhibitors now. Just in case.

Jake Moore

January 22, 2026 AT 05:13Great breakdown. For anyone reading this: if you’re over 60, have diabetes or vascular disease, and your doc wants to start you on an ACE inhibitor-ask for a baseline creatinine and a renal ultrasound before signing off. Seriously. It takes 5 minutes. Could save your kidneys. I’ve seen too many cases where this was missed.

christian Espinola

January 23, 2026 AT 11:31Typo in the post: 'efferent arteriole' is misspelled as 'efferent arteriole' in paragraph 3. Also, 'NICE guidelines' should be capitalized as 'NICE Guidelines'. And the study cited from 1984? It had a sample size of 15. That’s not statistically significant. You’re overgeneralizing.

Chuck Dickson

January 23, 2026 AT 14:56Hey everyone-this is important, but don’t freak out. Not everyone needs a scan. But if you’ve got high BP, high cholesterol, and you’re over 55? Get your creatinine checked before and 10 days after starting any ACE inhibitor. That’s it. Simple. Free. And it could catch something life-changing. Your doc owes you that much.

Naomi Keyes

January 24, 2026 AT 13:47Let’s be clear: the FDA’s contraindication is not a suggestion. It is a mandate. Additionally, the KDIGO guidelines are not 'recommendations'-they are evidence-based standards of care. Furthermore, the 2020 study referenced in the article is from JAMA Internal Medicine, not 'some study.' Precision matters. And if you’re ignoring these standards, you’re not just negligent-you’re endangering lives.

kenneth pillet

January 24, 2026 AT 14:20Been on amlodipine for 8 years. No issues. My doc checked my kidneys before even thinking about ACE stuff. Smart move. Don’t overthink it. Just ask for the blood test. Easy.

Jodi Harding

January 26, 2026 AT 07:11They don’t tell you this because it’s not profitable.

rachel bellet

January 28, 2026 AT 04:07It’s not just the efferent arteriole-it’s the entire RAAS cascade. The glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is pressure-dependent, and angiotensin II is the primary regulator of post-glomerular resistance. When you pharmacologically ablate that, you’re inducing afferent arteriolar dominance, leading to a precipitous drop in intraglomerular hydrostatic pressure. That’s not a side effect-it’s a hemodynamic catastrophe.

Ryan Otto

January 29, 2026 AT 23:08They don’t want you to know this because the entire pharmaceutical-industrial complex is built on this. The stenosis isn’t rare-it’s hidden. And the tests? Too expensive. So they let people die quietly. The same people who profit from dialysis machines are the ones who pushed these drugs. Coincidence? I think not.

Max Sinclair

January 30, 2026 AT 08:39Thanks for writing this. I’ve seen patients panic when their creatinine spikes and assume they’re doomed. But if caught early, recovery is totally possible. Just stop the drug, hydrate, monitor. Most bounce back. Don’t be scared-be informed. And if you’re a doc: check labs. Always.

Praseetha Pn

January 30, 2026 AT 21:53Y’all in the US think this is new? In India, we’ve been seeing this since the 90s-old men on lisinopril, kidneys crashing, docs blaming 'aging.' We call it 'Pharma Kidney Death.' We don’t wait for guidelines. We check creatinine before prescribing. Simple. Why don’t you?