Regulatory Exclusivity: How Non-Patent Protections Delay Generic Drugs

When a new drug hits the market, you might assume its high price is just because of patents. But that’s only half the story. Behind the scenes, there’s another powerful tool the FDA uses to block generics - one that has nothing to do with patents. It’s called regulatory exclusivity, and it’s what keeps competitors off the market for years, even after patents expire.

What Exactly Is Regulatory Exclusivity?

Regulatory exclusivity is a government-granted period during which the FDA can’t approve a generic or biosimilar version of a drug - no matter what. Unlike patents, which protect specific chemical structures or methods, exclusivity protects the drug itself. It doesn’t matter if someone invents a slightly different way to make it. If the drug is the same active ingredient, the FDA is legally barred from approving it until the exclusivity clock runs out.

This isn’t a reward for inventing something new - it’s a guarantee. You get it automatically when your drug is approved, as long as you meet the criteria. No lawsuits. No patent offices. Just a clock that starts ticking the moment the FDA signs off.

How Long Does It Last? The Key Types

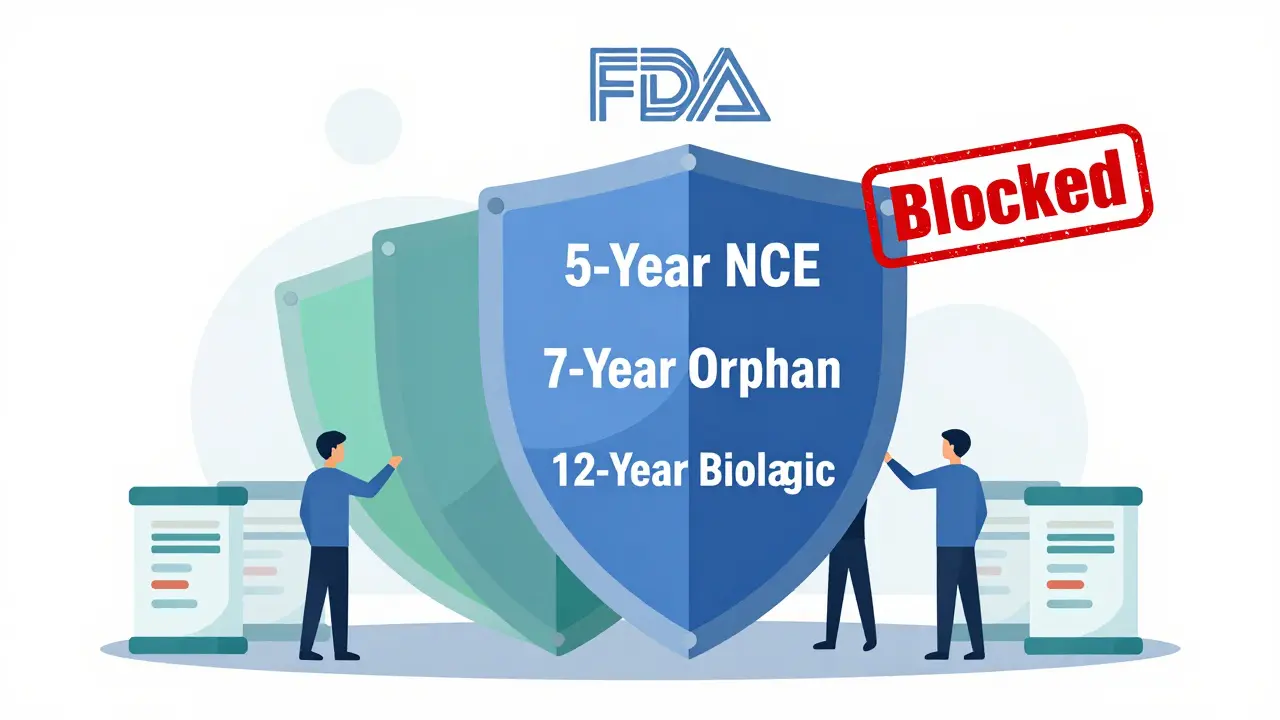

Not all exclusivity is the same. The FDA offers several types, each with different rules and durations:

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years. This is the most common. If your drug contains an active ingredient never before approved, you get 5 years of full protection. During the first 4 years, the FDA won’t even accept a generic application. At year 5, generics can be approved.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years. For drugs treating rare diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. This one’s powerful - even if another company develops the same drug for the same disease, they can’t get approval for 7 years.

- Biologics Exclusivity: 12 years. Created by the 2009 BPCIA law, this applies to complex protein-based drugs like Humira, Enbrel, or Keytruda. No biosimilar can enter the market for 12 years from the date of first approval.

- 3-Year Exclusivity: For new clinical studies that lead to changes in labeling - like adding a new use for an existing drug. This doesn’t block generics, but it stops competitors from copying your new indication.

These periods often stack. A drug might have 5 years of NCE exclusivity, 7 years of orphan status, and 12 years of biologics protection - all running at the same time. The longest one wins.

Why Does This Matter? The Real-World Impact

Take Humira. Its main patent expired in 2016. But because it’s a biologic, it got 12 years of regulatory exclusivity. That meant no biosimilars could enter the U.S. market until 2023. In 2022, AbbVie made nearly $20 billion in U.S. sales from Humira alone. That’s not just profit - that’s a monopoly enforced by law.

Compare that to a regular pill. If it’s a New Chemical Entity, generics can come in after 5 years. But for biologics? 12 years. That’s longer than most patents last. And since biologics take 10-15 years to develop, companies often get almost their entire commercial life under exclusivity - not patent protection.

This isn’t theoretical. In 2023, 88% of all new molecular entities approved by the FDA qualified for at least one form of regulatory exclusivity. That’s almost every new drug.

Exclusivity vs. Patents: The Big Differences

It’s easy to confuse exclusivity with patents. Here’s how they’re different:

| Feature | Regulatory Exclusivity | Patent Protection |

|---|---|---|

| Granted by | Food and Drug Administration (FDA) | U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) |

| Starts when | Drug is approved | Patent is issued (often years before approval) |

| Duration | Fixed: 5, 7, 12 years depending on type | 20 years from filing date |

| Enforcement | Automatic - FDA blocks approval | Company must sue infringers |

| Scope | Protects the drug product, regardless of patent claims | Protects specific inventions, formulas, or methods |

| Can be challenged? | No - unless the FDA made a mistake | Yes - through court litigation |

Patents can be invalidated in court. Exclusivity? Not unless the FDA messed up the paperwork. That’s why big pharma companies say: "Exclusivity is our most reliable protection. Patents get challenged. Exclusivity doesn’t."

Global Differences: What Other Countries Do

The U.S. isn’t the only player. Other countries have their own rules:

- European Union: Uses an "8+2+1" system - 8 years of data protection, 2 years of market exclusivity, and a possible 1-year extension for new uses.

- Japan: Grants 10 years of data exclusivity for new chemical entities.

- Canada: 8 years of data protection, but no market exclusivity - generics can submit applications earlier.

The EU is trying to shorten its exclusivity periods to speed up generic access. In 2023, they proposed cutting data exclusivity from 8 to 6 years. The U.S. hasn’t followed - yet.

Who Benefits? Who Loses?

The system was designed to balance two goals: reward innovation and allow competition. But in practice, the scales are tipped.

Originator companies love it. In a 2024 survey, 89% of big pharma said exclusivity is essential to recoup R&D costs. With a 12-year biologics term, they can charge premium prices for over a decade. IQVIA found that drugs under exclusivity sell for 3.2 times the price of generics.

But generic makers? Not so much. 68% of generic companies say exclusivity periods are too long, especially for biologics. The 4-year waiting period to even submit an application for an NCE forces them to start development blind - no data, no clarity, just risk.

And patients? They pay the price. A 2022 report by Public Citizen argued that extended exclusivity contributes to unsustainable drug prices. With biologics costing $100,000+ per year, delaying competition by 12 years means billions in extra spending by insurers and patients.

What’s Changing? The Future of Exclusivity

Pressure is building. Congress has tried multiple times to cut biologics exclusivity from 12 to 10 years. The Affordable Prescriptions for Patients Act of 2023 aimed to do just that. But lobbying from big pharma has stalled every attempt.

The FDA itself is updating its approach. In 2024, it released new guidance on how to calculate exclusivity for combination drugs - a growing category. And its 2024-2026 Drug Competition Action Plan says it wants to "modernize exclusivity frameworks to better balance innovation with timely generic competition."

Experts at Tufts CSDD predict that by 2030, the average combined patent and exclusivity period will drop from 12.3 years to 10.8 years. But biologics? They’ll likely keep their 12-year shield.

How Companies Use This System

Big pharma doesn’t just rely on one type of exclusivity. They layer them.

Take Humira again. It started as a New Chemical Entity - 5 years. Then it got orphan status for certain autoimmune conditions - 7 more years. And as a biologic, it got 12 years. The longest one - 12 years - controlled the market.

Companies also file multiple patents to create "patent thickets," then stack exclusivity on top. It’s a legal fortress. Even if one patent is broken, exclusivity still stands.

For smaller biotechs, exclusivity is a lifeline. Without it, they couldn’t compete with giants. But critics say the system is now being used to protect drugs that don’t need it - like minor tweaks to existing medicines.

Final Thoughts: A Necessary Tool or a Price Gouging Shield?

Regulatory exclusivity was meant to encourage innovation. And it did. Biologics, gene therapies, orphan drugs - many wouldn’t exist without this protection.

But today, it’s also a tool for extending monopolies far beyond what’s needed. The 12-year biologics term was designed for complex, hard-to-replicate drugs. But now, even simple protein drugs get the same protection.

As drug prices keep rising, the question isn’t whether exclusivity should exist - it’s whether it’s being used the way it was intended. The system works. But is it fair?

What’s the difference between patent and regulatory exclusivity?

Patents protect specific inventions - like a chemical formula or manufacturing method - and are enforced by lawsuits. Regulatory exclusivity protects the drug product itself and is enforced automatically by the FDA, which blocks generic approvals for a set period. Exclusivity starts at drug approval; patents start at filing, often years earlier.

Can a drug have both patent and exclusivity protection?

Yes, and most do. A drug can have a patent that expires in 2027 and regulatory exclusivity that lasts until 2030. The exclusivity period runs alongside the patent and can extend market protection even after the patent expires.

Why do biologics get 12 years of exclusivity?

Biologics are complex proteins made from living cells, not chemically synthesized. They’re harder to copy, require more testing, and take longer to develop. The 12-year term was designed to incentivize investment in these expensive, high-risk therapies. Critics argue it’s too long; supporters say it’s necessary to recoup R&D costs.

Does regulatory exclusivity apply outside the U.S.?

Yes, but rules vary. The EU uses an 8+2+1 system (8 years data protection, 2 years market exclusivity). Japan gives 10 years to new chemical entities. Canada has data protection but no market exclusivity. There’s no global standard.

Can generic companies challenge regulatory exclusivity?

Not directly. Unlike patents, exclusivity can’t be sued over. Generic companies can only challenge it if the FDA made a mistake - like granting exclusivity to a drug that doesn’t qualify. But proving that is extremely difficult. Most generics wait it out.

Frank Drewery

December 18, 2025 AT 16:02Man, I never realized how much of a backdoor this exclusivity stuff is. Patents get all the attention, but this FDA clock? That’s where the real monopoly happens. Makes you wonder how much of our drug prices are just legal loopholes.

Erica Vest

December 20, 2025 AT 13:22Regulatory exclusivity isn’t a loophole-it’s a statutory tool designed to incentivize innovation in high-risk areas like biologics and orphan drugs. The 12-year term for biologics was a compromise after years of debate; without it, investment in these therapies would collapse. Generic manufacturers aren’t harmed-they just need to plan better.

Kinnaird Lynsey

December 21, 2025 AT 13:36So let me get this straight… the FDA just says ‘nope’ to generics, no court, no proof, just ‘you’re not allowed’? And we call this a free market? 😏

Also, Humira’s $20B year? That’s not innovation-that’s a legalized tax on sick people.

Andrew Kelly

December 23, 2025 AT 07:32This whole system is a controlled demolition of competition. Big Pharma wrote these rules with Congress in their back pocket. The 12-year biologics term? A gift from lobbyists. The FDA doesn’t ‘make mistakes’-they’re complicit. Wake up: this isn’t regulation, it’s corporate feudalism.

And don’t tell me ‘it’s for innovation’-they’re just tweaking old drugs and calling them new. You think Humira’s a miracle? It’s a $100K/year placebo with a fancy name.

Connie Zehner

December 25, 2025 AT 05:11OMG I just read this and I’m CRYING 😭 Like… my mom’s on Humira and she pays $1,200/month and I just found out it COULD BE $300 if we weren’t being SCAMMED?? This is evil. Who do I sue??

Jedidiah Massey

December 26, 2025 AT 21:25Let’s deconstruct the economic externalities of non-patent market exclusivity frameworks vis-à-vis pharmaceutical R&D capital recovery curves. The 12-year biologics exclusivity window isn’t an anti-competitive artifact-it’s a necessary temporal arbitrage to internalize the high variance in clinical trial outcomes. The marginal cost of biosimilar development remains structurally higher than small-molecule generics, thus justifying extended exclusivity under first-mover incentive theory.

Also, your ‘price gouging’ narrative ignores opportunity cost. 🤓

Alex Curran

December 27, 2025 AT 11:11Interesting breakdown but you missed how Canada’s system works differently-no market exclusivity means generics can file earlier even if data is protected. That’s actually smarter. The US locks things up too tight. Also why is orphan drug exclusivity so broad? Could be abused for common conditions rebranded as rare. Just saying.

Lynsey Tyson

December 28, 2025 AT 06:59It’s wild how something so technical ends up costing people their health. I get why companies need to make money, but 12 years? That’s longer than my last relationship. Maybe we could find a middle ground?

Edington Renwick

December 29, 2025 AT 22:51They’re laughing at us. Every single one of them. The CEOs, the lobbyists, the FDA bureaucrats-they all know this is a scam and they’re milking it dry. And you? You’re still paying your co-pay like a good little sheep. Wake up. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a Ponzi scheme with IV drips.

anthony funes gomez

December 30, 2025 AT 22:07The structural tension between innovation incentives and distributive justice in pharmaceutical markets cannot be resolved through temporal adjustments alone. Exclusivity regimes function as rent-seeking mechanisms disguised as public policy instruments. The 12-year biologics term, while empirically justified under risk-adjusted return models, nonetheless entrenches asymmetrical power relations between capital and care. We must interrogate not duration, but the ontology of value: Is a drug’s worth measured in patent-years or in lives restored? The answer reveals the moral bankruptcy of the system.

Alana Koerts

January 1, 2026 AT 00:37Most of this is just regurgitated pharma PR. 12 years? That’s a joke. Half the biologics approved get exclusivity even if they’re just rehashes of older drugs. And don’t get me started on orphan drug abuse-companies are gaming the 200k patient threshold like it’s a video game. Lazy reporting.

pascal pantel

January 1, 2026 AT 21:01Let’s be real: this isn’t about innovation. It’s about profit maximization under legal camouflage. The 4-year waiting period to even submit a generic application? That’s not protection-it’s sabotage. And the FDA? They’re not neutral. They’re a rubber stamp for Big Pharma. We’re being fleeced. Period.

Gloria Parraz

January 2, 2026 AT 16:27You know what? This is why I’m so proud of the work we do in patient advocacy. People like you who take the time to understand these systems? You’re the ones who change things. Keep speaking up. One day, we’ll get fair access. I believe in you. 💪