NTI-Specific Substitution Laws: Which States Have Special Rules for Critical Medications

When you pick up a prescription for a drug like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin, you might assume the pharmacist can swap the brand name for a cheaper generic. But in many states, that’s not allowed - not because the generic doesn’t work, but because the law says so. These are NTI drugs: Narrow Therapeutic Index medications where even tiny differences in dosage can cause serious harm. A little too much warfarin could trigger a stroke. A little too little levothyroxine might leave you exhausted, depressed, or at risk for heart failure. And that’s why 27 states have passed special rules to block or restrict generic substitution - even though the FDA says these generics are just as safe.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

NTI stands for Narrow Therapeutic Index. That means the difference between a dose that works and a dose that’s dangerous is razor-thin. The FDA doesn’t officially label drugs as NTI - it doesn’t even maintain a public list. But pharmacists and doctors know the big ones: digoxin, lithium, warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and cyclosporine. These aren’t just any pills. They’re the kind where a 10% change in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis.

Here’s the catch: generic drugs are required to be bioequivalent to the brand name. That means their blood levels should fall within 80-125% of the original. For most drugs, that’s fine. For NTI drugs, that 45% window is wide enough to cause problems. A patient stable on brand-name warfarin might switch to a generic and suddenly have an INR that spikes from 2.5 to 4.2 - putting them at risk for bleeding. Or their thyroid levels might drop, making them feel sluggish for weeks. That’s why some states decided to step in.

How States Handle NTI Substitution Differently

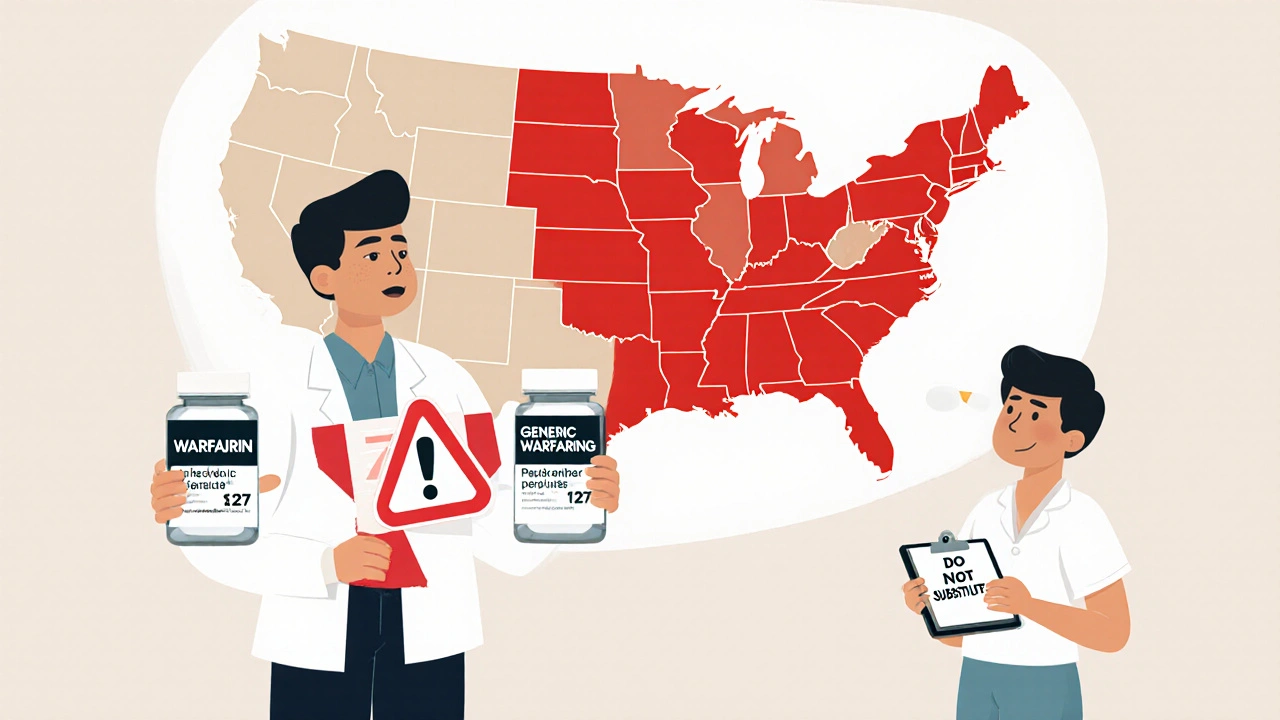

There’s no national rule. Instead, you’ve got a patchwork of 27 state laws with three main approaches:

- Carve-outs: The drug is completely off-limits for substitution. Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina are examples. If it’s on their list, the pharmacist can’t switch it - not even if you ask.

- Dual consent: Both you and your doctor must sign off. North Carolina requires written permission from both before any substitution. Connecticut goes further: if you’re on an anti-seizure drug, the pharmacist must notify your doctor and you within 72 hours, and either of you can block the switch within 14 days.

- Notification only: The pharmacist can substitute, but must document it and tell your doctor. States like South Carolina and Maryland use this model. It’s less restrictive, but still adds paperwork.

Some states go even further. Kentucky’s list includes specific formulations - not just “warfarin,” but “warfarin sodium tablets, all strengths.” That means even if you’ve been on a generic for years, if the pharmacy runs out of the exact brand you’re on, they can’t swap it for another generic unless your doctor approves. That creates real delays. One pharmacist in Louisville told me they spend 5-7 extra minutes per NTI prescription just checking the list.

Which States Block Substitution Altogether?

These states have the strictest rules - they don’t allow substitution unless the prescriber explicitly says yes:

- Kentucky: Has the most detailed list. Prohibits substitution for digoxin, levothyroxine, lithium, and warfarin. Requires written authorization from the prescriber for any exception.

- Pennsylvania: Maintains a formal NTI list. No substitutions allowed without prescriber approval.

- North Carolina: Requires written consent from both patient and prescriber before any NTI substitution.

- Connecticut: Special rules for anti-epileptic drugs. Requires notification and allows objections from either patient or doctor.

- Illinois: Requires patient consent, but prescriber consent is not mandatory.

Meanwhile, states like California, Texas, and Virginia follow federal guidelines. If the FDA says it’s therapeutically equivalent, the pharmacist can substitute. No extra forms, no special lists. That’s led to much faster fill times and lower costs - but also more anxiety among patients who’ve had bad experiences.

Why the Conflict Between FDA and State Laws?

The FDA says all approved generics, including for NTI drugs, meet the same quality standards. They’ve reviewed thousands of studies and found no consistent evidence that generic NTI drugs cause more adverse events. A 2020 study of over 12,000 Medicare patients on warfarin showed no difference in bleeding risk between brand and generic.

But doctors and pharmacists on the front lines see something different. A 2021 study in the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association found states with NTI restrictions had 28.7% fewer reported adverse events. That doesn’t prove the laws prevent harm - but it suggests they might. Many patients report feeling unstable after switching. One woman in Ohio told her doctor she had three seizures in two weeks after her pharmacy switched her from brand-name phenytoin to a generic. Her INR levels were normal. Her seizure threshold wasn’t.

Dr. Aaron Kesselheim from Harvard puts it simply: “The FDA looks at averages. Clinicians look at individuals.”

What This Means for Patients

If you take an NTI drug, your experience depends entirely on where you live.

- In Kentucky, you’ll get the same brand or generic every time - unless your doctor changes it.

- In Texas, you might get a different generic every refill, and the pharmacy won’t tell you unless you ask.

- In North Carolina, you’ll get a consent form to sign before each refill.

That inconsistency creates confusion. Patients often don’t know whether they’re allowed to switch. Pharmacists struggle to keep up with 27 different rules. One chain pharmacy manager in Virginia said their system automatically substitutes all generics - including NTI drugs - and they’ve had fewer than 0.5% complaints. Another pharmacist in Pennsylvania said they spend nearly 9 extra hours a month just checking NTI lists and filling out paperwork.

Cost is another factor. States with strict substitution rules have 12.4% lower generic use for NTI drugs. That means more people pay full price for brand-name drugs. In 2022, NTI prescriptions totaled $28.7 billion in the U.S. - and billions of that went to brand-name manufacturers because state laws blocked cheaper alternatives.

What’s Changing Now?

The landscape is shifting. The FDA released draft guidance in 2023 suggesting a clearer way to define NTI drugs - using a ratio of toxic to effective dose. Nine states, including New York and Ohio, are now considering updating their lists based on this new standard.

California passed a law in 2022 requiring any NTI designation to be backed by clinical evidence, not just tradition. That’s a big deal. Many drugs on state lists - like Premarin or Synthroid - aren’t even classified as NTI by scientific review. A 2021 study found only 12 of the 47 drugs on state NTI lists had solid evidence supporting their narrow index.

There’s also legal pressure. In 2023, the Association for Accessible Medicines sued Kentucky, arguing its list violates the Dormant Commerce Clause by making it harder for out-of-state generics to compete. The case is ongoing.

Meanwhile, the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy is working on a model state law to bring some consistency. But with states fiercely protective of their right to regulate pharmacy practice, full national alignment is unlikely.

What You Should Do

If you’re on an NTI drug, here’s what to do right now:

- Know your state’s rules. Check your state pharmacy board’s website. Look for “NTI substitution” or “generic substitution exceptions.”

- Ask your pharmacist. “Is this drug on my state’s restricted list?” If they say yes, ask if you can stay on your current version.

- Talk to your doctor. If you’ve had issues after a switch, tell them. Request a “do not substitute” note on your prescription.

- Keep a log. Write down how you feel after each refill. If you notice changes in energy, mood, or symptoms, bring it up.

- Don’t assume. Just because your friend got a generic doesn’t mean you can. Your state might be different.

NTI drugs aren’t the same as other prescriptions. They demand attention. Whether your state lets you switch or locks you into one brand, the goal is the same: keep your levels stable. Don’t let cost or convenience override safety - but don’t pay more than you have to, either. Know your rights. Know your meds. And don’t be afraid to ask questions.

Are generic NTI drugs really as safe as brand-name ones?

The FDA says yes - all approved generics must meet the same bioequivalence standards. But real-world data shows mixed results. Some patients report instability after switching, especially with warfarin or levothyroxine. Studies show no clear increase in adverse events overall, but for individuals with sensitive conditions, even small changes can matter. The FDA looks at population averages; doctors treat individual patients.

Can I request to stay on my brand-name NTI drug?

Yes. In every state, you can ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute” on your prescription. This legally prevents the pharmacist from switching you, even in states with no NTI restrictions. Some pharmacies charge a small fee for brand-name fills, but it’s your right to choose.

Why do some states restrict substitution if the FDA says it’s safe?

State laws are based on clinical experience, not federal guidelines. Pharmacists and doctors in states with restrictions have seen patients have seizures, bleeding episodes, or thyroid crashes after switching generics. Even if those cases are rare, the potential consequences are severe. States prioritize caution over cost savings, especially for drugs where mistakes can be life-threatening.

Which NTI drugs are most commonly restricted?

The most commonly restricted NTI drugs are warfarin (blood thinner), levothyroxine (thyroid hormone), lithium (mood stabilizer), digoxin (heart medication), phenytoin, and carbamazepine (anti-seizure drugs). These appear on nearly every state’s restricted list. Some states also include cyclosporine and tacrolimus - drugs used after organ transplants.

How do I find out if my state has NTI substitution rules?

Visit your state’s Board of Pharmacy website. Search for “generic substitution,” “NTI drugs,” or “therapeutic equivalence.” Many states have downloadable lists or FAQs. If you can’t find it, call the board directly - they’re required to answer public questions. You can also ask your pharmacist: they’re trained on your state’s rules.

jim cerqua

November 21, 2025 AT 22:21This is why America’s healthcare system is a goddamn circus. You’ve got pharmacists playing gatekeeper to life-saving meds because some state legislature decided to panic over a handful of anecdotal horror stories. Meanwhile, real people are choosing between rent and their $400/month brand-name thyroid pill. The FDA says it’s safe. Doctors say it’s safe. But nope - let’s make everyone jump through 27 different bureaucratic hoops just so some politician can look like they’re ‘protecting patients.’

Julia Strothers

November 22, 2025 AT 23:27They’re lying. All of them. The FDA? Controlled by Big Pharma. The ‘studies’? Funded by generic manufacturers. I’ve seen it - people switch to generics, then end up in the ER with seizures or internal bleeding. They don’t tell you that the generics aren’t made in the same clean rooms. The active ingredient? Same. The fillers? Toxic sludge from China. And now they want to force us to take it? No. Not in my state. Not ever.

Anne Nylander

November 24, 2025 AT 20:19Y’all just need to talk to your doc and ask for ‘do not substitute’!! It’s super easy!! My grandma’s on levothyroxine and she’s been on the same brand for 12 years because she asked!! No drama!! You got rights!! 😊

Leo Tamisch

November 26, 2025 AT 09:43It’s not about safety - it’s about epistemological humility. The FDA operates on statistical abstraction, a Cartesian fantasy of the body as a machine with predictable variables. But human physiology is a chaotic, nonlinear system. A 10% fluctuation in blood levels may be statistically insignificant - yet for a single individual, it may be the difference between equilibrium and collapse. The state laws, however irrational they appear, are an acknowledgment of this irreducible complexity. We are not data points. We are organisms. And reductionism, however elegant, fails here.

Donald Frantz

November 27, 2025 AT 00:04Let’s cut through the noise. The FDA’s bioequivalence range of 80-125% is absurd for NTI drugs. That’s a 45% swing - equivalent to letting someone drive a car with a gas pedal that can go from 0 to 120 mph with a light tap. If your car’s speedometer had that kind of error, you’d sue the manufacturer. Why are we accepting this for drugs that keep people alive? The real issue isn’t state vs federal - it’s that the regulatory standard is dangerously outdated. Time to redefine NTI thresholds with real clinical data, not 1980s math.

Corra Hathaway

November 28, 2025 AT 17:34OMG I just found out my state (Ohio) is updating their list?? 😭 I’ve been on carbamazepine for 8 years and switched generics last year - I had 3 migraines in a week and felt like I was underwater. My neurologist said ‘stick with brand’ and now I’m stable again. THANK YOU for writing this - I’ve been too scared to tell anyone I think the generic made me sick. Also, why do we even have 27 different rules?? Can’t we just… agree?? 🤦♀️

Franck Emma

November 29, 2025 AT 18:33My sister died after a switch. Generic phenytoin. INR normal. Seizures every 3 hours. They told her it was ‘just a coincidence.’

Simone Wood

December 1, 2025 AT 02:51Have you considered that the real reason states restrict substitution is because Big Pharma bribed legislators? I mean, look at Kentucky - they’ve got the most restrictive list. Coincidence? Or is it because the brand-name manufacturer is headquartered in Louisville? The paperwork? The delays? It’s all designed to keep generics out. You think pharmacists care about your INR? They care about their commission on brand-name sales. Wake up.

Pravin Manani

December 2, 2025 AT 13:59From a clinical pharmacology standpoint, the core issue lies in the pharmacokinetic variability of NTI agents under real-world conditions. Bioequivalence, as defined by AUC and Cmax, assumes steady-state conditions - but patients are non-adherent, have comorbidities, take polypharmacy, and experience GI variability. The 80–125% window, derived from healthy volunteers, is inadequate for populations with hepatic polymorphisms or malabsorption syndromes. The state-level restrictions, while fragmented, reflect a pragmatic response to clinical heterogeneity. The FDA’s population-level data does not capture individual pharmacodynamic susceptibility - particularly in elderly or polypharmacy patients. A harmonized, evidence-based NTI classification - calibrated to pharmacogenomic risk stratification - would be the ideal solution. Until then, physician discretion and patient autonomy must remain paramount.

Daisy L

December 2, 2025 AT 21:10So let me get this straight - if I’m on warfarin in Texas, I could get a different generic every time - and the pharmacy doesn’t even have to tell me?? And if I’m in Kentucky, I’m stuck with the same pill - even if it costs 10x more?? This isn’t healthcare - it’s Russian roulette with my life. And the worst part? I’m supposed to be grateful that someone’s ‘protecting’ me - while my insurance company pockets the extra $300 a month. I’m not a lab rat. I’m a person. And I deserve to know what’s in my damn pill.