Insulin Biosimilars: What You Need to Know About Cost, Safety, and Market Options

Diabetes affects over 500 million people worldwide, and insulin is one of the most essential treatments. But for many, the cost is unbearable - sometimes over $400 a month for a single vial. That’s where insulin biosimilars come in. They’re not generics. They’re not copies. They’re highly similar versions of brand-name insulins, proven to work just as well, but at a fraction of the price. Yet, despite their promise, adoption has been slow. Why? And which ones are actually available right now?

What Exactly Are Insulin Biosimilars?

Insulin biosimilars are complex biological products made to match the structure and function of an already-approved insulin, called the reference product. Think of them like a close cousin, not a twin. Unlike generic pills - which are chemically identical to their brand-name counterparts - biosimilars are made from living cells. That means tiny differences can happen during production. But here’s the key: these differences don’t affect safety or effectiveness.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) require years of testing to approve them. That includes analyzing molecular structure, running lab tests, studying how the body absorbs the insulin, and conducting clinical trials on thousands of patients. The goal? Prove there’s no meaningful difference in how well it lowers blood sugar or how safe it is.

For example, Basaglar is a biosimilar to Lantus (insulin glargine). Semglee is another. Both have been shown in multiple studies to control A1C levels just as well as the original. In one 2024 trial, patients switching from Lantus to Semglee saw no increase in hypoglycemia or weight gain. Their blood sugar stayed steady.

Biosimilars vs. Generics: The Big Difference

It’s easy to assume biosimilars are just cheaper generics. They’re not. Generics are simple molecules made in a lab - think metformin or lisinopril. Biosimilars are large, complex proteins made in living cells, like insulin, antibodies, or growth hormones. Because of this complexity, you can’t make an exact copy. You can only make a very, very close version.

That’s why the approval process for biosimilars is longer and more expensive. A generic can be approved in a year or two. A biosimilar takes five to seven. But the payoff? A 15-30% cost reduction. For insulin, that’s hundreds of dollars a month saved.

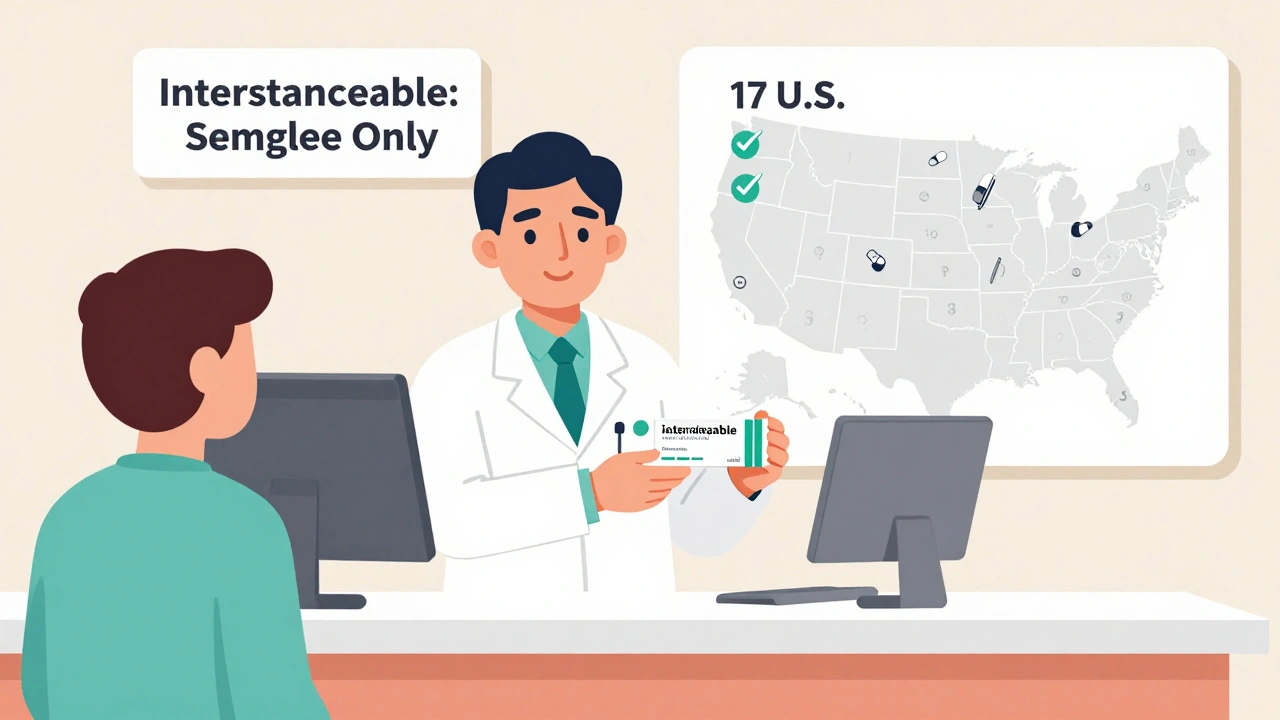

And here’s something most people don’t realize: the FDA doesn’t automatically consider biosimilars interchangeable. Only a few insulin biosimilars have that extra designation. Interchangeable means a pharmacist can switch you from the brand to the biosimilar without asking your doctor. As of early 2025, only Semglee has that status in the U.S. Basaglar does not. That’s a huge barrier to wider use.

Market Examples: Which Biosimilars Are Actually Available?

As of 2025, six insulin biosimilars are approved in the European Union. In the U.S., the list is shorter but growing. Here are the key players:

- Semglee (insulin glargine-yfgn) - Biosimilar to Lantus. First interchangeable insulin biosimilar approved by the FDA in 2021. Sold by Mylan and Biocon. Average monthly cost: $90-$110 vs. $450+ for Lantus.

- Basaglar (insulin glargine) - Also a biosimilar to Lantus. Approved in 2019. Not interchangeable. Sold by Eli Lilly. Costs about $100-$130 per month.

- Admelog (insulin lispro) - Biosimilar to Humalog. Approved in 2019. Used for mealtime insulin. Costs around $120-$150 per vial.

- Rezvoglar (insulin glargine-aglr) - Another Lantus biosimilar, approved in 2023. Not interchangeable. Priced similarly to Basaglar.

- Huizuma (insulin glargine) - A newer entrant from BGP Pharma, approved in 2024. Available in select markets.

- Abasaglar (insulin glargine) - Marketed in Europe and parts of Asia. Same active ingredient as Basaglar.

Companies like Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk are still the biggest names in insulin. But now, Biocon, Samsung Bioepis, and Mylan are gaining ground. In India, where insulin costs can be 70% lower with biosimilars, adoption is soaring. In Mumbai, one endocrinologist reported that 45% of his patients now use biosimilar insulins.

Why Aren’t More People Using Them?

Despite the savings and proven safety, insulin biosimilars have only captured about 26% of the market after five years. Compare that to oncology biosimilars, which hit 81% market share in the same time. Why the gap?

First, fear. Many patients and doctors worry about switching. One Reddit user reported more frequent low blood sugars after switching to a biosimilar - a concern that’s real, even if rare. The American Diabetes Association’s community forum has dozens of stories like that. But most users - 68% according to a 2025 survey - report no change in how they feel or how their blood sugar responds.

Second, confusion. Pharmacists can’t automatically substitute biosimilars in most states. Only 17 states in the U.S. allow it for insulin. In the rest, your doctor must write a new prescription every time. That’s a paperwork nightmare.

Third, marketing. Sanofi still sells both branded Lantus and a cheaper, unbranded version - essentially undercutting biosimilars before they even launch. Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk have done similar things, offering discounts and patient assistance programs that make the original brand look like the better deal.

How to Switch Safely

If you’re thinking about switching, don’t do it on your own. Talk to your doctor. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists recommends a 3-6 month transition period with close monitoring. That means checking your blood sugar more often - especially in the first few weeks.

Some people need a slight dose adjustment. Insulin biosimilars can have minor differences in how fast they start working or how long they last. For example, one study found that Semglee peaked slightly earlier than Lantus in some patients. That doesn’t mean it’s less safe - just that timing matters. Your doctor might tweak your injection schedule or meal plan.

Keep a log. Write down your blood sugar readings, any low episodes, and how you feel. Bring it to your next appointment. Most endocrinologists say once patients get past the first month, they’re just as stable - if not more so - on biosimilars.

Cost and Insurance: What You’ll Actually Pay

In 2025, the average selling price for insulin biosimilars in the U.S. was $1,840 per year - about 60% less than the reference product. But that’s the wholesale price. What you pay depends on your insurance.

Medicare Part D now reimburses pharmacies at the biosimilar’s average selling price plus 8%. That’s a big incentive for pharmacies to stock them. Many private insurers have followed suit. If you’re on Medicaid or have a high-deductible plan, ask if your pharmacy offers a cash price. Some biosimilars cost as little as $25 a month with coupons.

And here’s the kicker: the U.S. holds nearly 30% of the global insulin biosimilar market. That’s because of high drug prices and massive patient demand. In countries like Germany and India, government-backed programs are pushing biosimilars hard. In India, they’re now the default option for public hospitals.

The Future: What’s Coming Next

The insulin biosimilar market is expected to grow at 18% per year through 2034 - triple the rate of other biosimilars. Why? Because major patents are expiring. By 2026, biosimilars for Toujeo and Tresiba will hit the market. That’s two more high-cost, long-acting insulins that could drop in price.

Manufacturers are also working on smarter delivery systems. Over 78% of companies are now combining biosimilars with connected pens and apps that track doses and blood sugar. That’s a game-changer for adherence.

Regulators are starting to align. The FDA and EMA are working on shared standards to speed up approvals. That could cut development time by over a year. And with global diabetes cases expected to hit 783 million by 2045, the pressure to make insulin affordable will only grow.

Right now, insulin biosimilars are the most promising tool we have to make diabetes care sustainable. They’re safe. They work. And they’re saving lives - especially in places where people used to ration insulin.

But they won’t fix the system alone. Patients need education. Doctors need clarity. Pharmacists need legal freedom to substitute. And insurers need to stop favoring expensive brands.

For now, if you’re paying more than $100 a month for insulin, ask your doctor: is a biosimilar right for you? The answer might just change your life.

Are insulin biosimilars safe?

Yes. Insulin biosimilars undergo the same rigorous testing as the original products, including clinical trials involving thousands of patients. Studies show no meaningful difference in safety or effectiveness. The FDA and EMA only approve them after proving they work just as well and carry the same risks - like low blood sugar - as the reference insulin. Serious side effects are rare and similar across all versions.

Can I switch from my current insulin to a biosimilar?

You can, but you should only do it under your doctor’s supervision. Most guidelines recommend a 3-6 month transition with close blood sugar monitoring. Some people need small dose adjustments. Never switch on your own. If you’ve had stable blood sugar for months, your doctor can help you choose a biosimilar that matches your needs.

Is Semglee better than Basaglar?

Both are biosimilars to Lantus and work similarly. The main difference is interchangeability. Semglee is FDA-approved as interchangeable, meaning a pharmacist can switch you to it without a new prescription. Basaglar is not. That makes Semglee easier to access in many states. Cost-wise, they’re very close - both usually under $100 a month with insurance or coupons.

Why don’t pharmacies automatically substitute biosimilars?

Because only 17 U.S. states allow pharmacists to substitute insulin biosimilars without a doctor’s note. In the other 33, the law requires a specific prescription for each product. This is due to lingering concerns about safety and liability. Even though science supports substitution, legal and insurance rules haven’t caught up. That’s changing slowly as more data comes in.

Do insulin biosimilars cause more allergic reactions?

No. Studies have found no increase in allergic reactions or immunogenicity with insulin biosimilars compared to the original products. The manufacturing process ensures the protein structure is nearly identical. While any insulin can cause mild skin reactions at the injection site, this is unrelated to whether it’s a biosimilar or brand name. If you’ve never had a reaction to your current insulin, you’re unlikely to have one with a biosimilar.

Will my insurance cover insulin biosimilars?

Most do - and many prefer them because they’re cheaper. Medicare Part D pays pharmacies 8% above the biosimilar’s average price, which encourages stocking them. Private insurers often have lower copays for biosimilars. Always check your plan’s formulary. If your current insulin is expensive, ask your doctor to prescribe a biosimilar. Many patients save $300-$400 a month.

What’s Next for You?

If you’re paying over $100 a month for insulin, you’re not alone - and you’re not stuck. Ask your doctor about biosimilars. Check your insurance formulary. Look up Semglee or Basaglar. Ask your pharmacy for cash prices. The savings are real. The science is solid. The only thing holding you back is the belief that you have to pay the full price. You don’t.

Amber-Lynn Quinata

December 3, 2025 AT 02:13Lauryn Smith

December 4, 2025 AT 16:17Bonnie Youn

December 5, 2025 AT 07:45Rachel Stanton

December 7, 2025 AT 02:02Edward Hyde

December 8, 2025 AT 17:44Charlotte Collins

December 9, 2025 AT 22:44Margaret Stearns

December 11, 2025 AT 08:35Scotia Corley

December 12, 2025 AT 10:32Kenny Leow

December 13, 2025 AT 20:27