Indian Generic Manufacturers: The World's Pharmacy and Exports

India’s Generic Drug Industry: Powering Global Healthcare

When you pick up a bottle of amoxicillin, metformin, or a blood pressure pill in the U.S., Europe, or sub-Saharan Africa, there’s a strong chance it came from India. The country doesn’t just make generic drugs-it supplies them to nearly every corner of the world. With over 60,000 generic medicines produced annually, India is the largest provider of generic pharmaceuticals by volume, accounting for 20% of global exports. This isn’t luck. It’s the result of deliberate policy, low-cost manufacturing, and decades of regulatory evolution.

How India Became the Pharmacy of the World

The story starts in the 1970s. India changed its patent laws to allow companies to copy branded drugs after the original patent expired. This wasn’t piracy-it was legal, strategic, and designed to make life-saving medicines affordable. Before this, a single course of HIV medication could cost $10,000. Indian manufacturers cut that to under $100. By the early 2000s, countries like South Africa and Brazil were relying on Indian generics to treat millions of HIV patients. Today, that same model applies to diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and vaccines.

India’s advantage isn’t just price. It’s scale. The country has more than 10,000 manufacturing facilities and over 650 FDA-approved plants-more than any other country outside the U.S. That’s why the U.S. gets 40% of its generic drugs from India. The U.K. gets 33%. Sub-Saharan Africa relies on India for 50% of its medicines. No other nation comes close in volume or reach.

Quality: From Skepticism to Global Trust

For years, Indian generics faced criticism. Reports of substandard batches surfaced in the U.S. and Europe. In 2015, only about 60% of Indian plants passed FDA inspections. But things changed. By 2024, compliance rates hit 85-90%-matching global averages. Why? Because the biggest players couldn’t afford to fail. If a single batch of insulin or a heart drug failed inspection, it could cost millions in lost contracts.

Companies like Sun Pharma, Cipla, and Dr. Reddy’s now invest 6-8% of their revenue in R&D and quality systems. They’ve adopted electronic common technical documents (eCTD), trained inspectors, and automated production lines. Today, Indian manufacturers produce complex generics-extended-release tablets, transdermal patches, and sterile injectables-that require precision engineering. The FDA doesn’t treat them as low-cost outliers anymore. They’re treated as equals.

Who’s Buying? The Global Demand Breakdown

India doesn’t just sell to rich countries. It sells to the people who need it most.

- In the U.S., Indian generics make up 40% of all prescriptions filled for generic drugs. PharmacyChecker.com shows 87% patient satisfaction, with affordability cited as the top reason.

- In the U.K., the NHS relies on Indian suppliers for 33% of its generic medicines. Patient reviews on NHS Choices average 4.2 out of 5, though some complain about taste or packaging differences.

- In Africa, organizations like Doctors Without Borders use Indian-made antimalarials and antibiotics because they’re 65% cheaper and still maintain 95% efficacy in real-world conditions.

It’s not just about cost. It’s about access. Without Indian generics, millions in low-income countries wouldn’t get treatment at all.

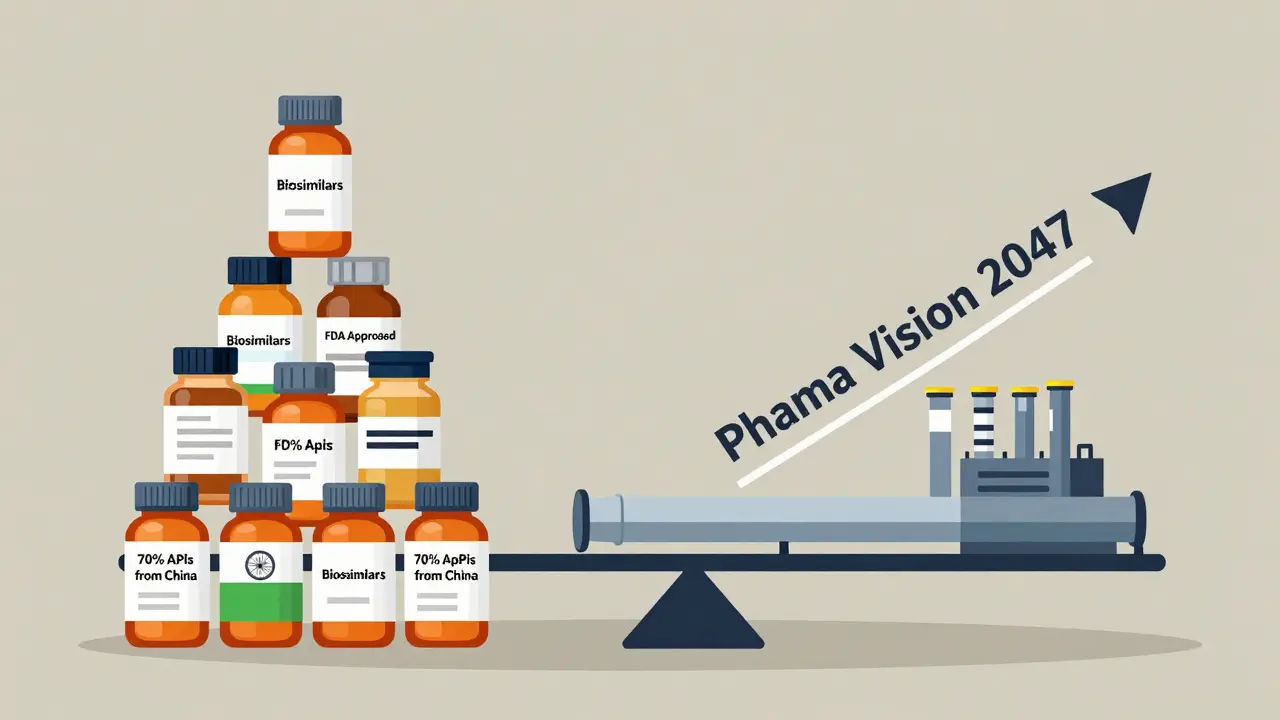

The Hidden Weakness: Dependence on China

Despite its strengths, India has a critical flaw: it still imports 70% of its active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from China. APIs are the core chemical components that make drugs work. Without them, no pills are made.

This dependency became a crisis during the pandemic. When China shut down factories in 2020, India faced shortages of antibiotics, paracetamol, and even vitamin B12. The government responded with a ₹3,000 crore ($400 million) Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme to build domestic API capacity. The goal? Reduce Chinese reliance to 53% by 2026.

But building API plants isn’t easy. It takes $100 million and five years to set up a single facility. India has made progress, but it’s still behind. Until it becomes self-sufficient, its pharmaceutical dominance remains vulnerable to geopolitical shocks.

India vs. China: Why Volume Doesn’t Equal Value

China makes more APIs than India. It’s cheaper. But China doesn’t have the same regulatory track record. The U.S. FDA has approved only 153 Chinese plants compared to India’s 650. That’s why global buyers choose India-not because it’s the cheapest, but because it’s the most reliable.

Still, India earns far less per unit than it should. It supplies 30% of the U.S. generic market by volume but only 10% by value. Why? Because it sells low-margin, high-volume drugs. Companies like Teva and Sandoz make more money selling the same pills at higher prices in Europe. India’s challenge isn’t production-it’s pricing power.

The Future: From Generics to Biosimilars

India’s next big move is biosimilars-highly complex, biotech-derived versions of expensive cancer and autoimmune drugs. These aren’t simple pills. They’re living molecules made in bioreactors. They require labs, not factories.

Companies like Biocon and Dr. Reddy’s are investing over $500 million annually in biosimilar research. In 2020, biosimilars made up just 3% of India’s export value. By 2024, that jumped to 8%. The goal? Reach 20% by 2030.

If India succeeds, it won’t just be the pharmacy of the world. It’ll be the innovation hub for affordable biologics. That’s the real test: moving beyond copying to creating.

Real-World Challenges: What Goes Wrong

Not every batch is perfect. Reddit threads and Trustpilot reviews show real complaints:

- Some users report inconsistent dissolution rates in Indian-made levothyroxine (a thyroid drug).

- Shipping delays hit 23% of negative reviews.

- Packaging inconsistencies (wrong labels, missing inserts) show up in 17% of complaints.

These aren’t safety issues-they’re operational ones. They happen because Indian exporters often ship to dozens of countries with different labeling rules. A batch meant for Brazil might get mislabeled for Nigeria. The fix? Better digital tracking and standardized packaging systems. Most large manufacturers are already doing this. Smaller ones still struggle.

What’s Next for India’s Pharma Sector

The Indian government launched Pharma Vision 2047-a plan to make the country’s pharmaceutical exports hit $190 billion by 2047. That’s more than double today’s value. To get there, three things must happen:

- API self-sufficiency must rise above 50%.

- Biosimilars and complex generics must replace low-margin tablets.

- Regulatory compliance must hit 95% or higher.

India has the talent. It has the infrastructure. It has the global trust. What it needs now is focus. Not just on making more pills-but on making better ones.

Are Indian generic drugs safe to use?

Yes, the vast majority are. Over 650 Indian manufacturing plants are approved by the U.S. FDA, and more than 2,000 meet WHO-GMP standards. Compliance rates have improved from 60% in 2015 to over 85% today. While isolated cases of substandard batches have occurred, they’re rare and usually traced to smaller, unregulated exporters-not major manufacturers. Always buy from licensed pharmacies or verified online suppliers.

Why are Indian generic drugs so much cheaper?

India eliminated product patents for drugs in the 1970s, allowing local companies to copy branded medicines without paying licensing fees. Combined with low labor costs, efficient supply chains, and high production volumes, this creates massive savings. A drug that costs $500 in the U.S. might cost $50-$100 from India. The active ingredient is identical-just the brand name and packaging differ.

Does the U.S. rely on India for its generic drugs?

Absolutely. India supplies about 40% of all generic drugs dispensed in the U.S., including common medications like metformin, lisinopril, and atorvastatin. Major U.S. pharmacies and insurers source these drugs directly from Indian manufacturers because they’re reliable and cost-effective. Without them, many Americans would pay far more for prescriptions.

How do Indian generics compare to Chinese ones?

China produces more active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and at lower prices, but India leads in finished drug manufacturing with far more FDA-approved facilities (650 vs. 153). Indian drugs are more trusted by Western regulators and healthcare systems because of better quality control and compliance. China’s exports are often bulk APIs; India’s are ready-to-use pills, injections, and vaccines.

Can India become a leader in drug innovation, not just manufacturing?

Yes, and it already is-just not in the way most people expect. India isn’t inventing new chemical molecules like Pfizer or Roche. But it’s pioneering affordable versions of complex biologic drugs called biosimilars. Companies like Biocon and Dr. Reddy’s are developing biosimilars for cancer and autoimmune diseases at a fraction of the cost. If they succeed, India won’t just be the world’s pharmacy-it’ll be the world’s source of affordable biotech innovation.

Stephen Craig

January 5, 2026 AT 10:59India's generic drug model proves that scale and regulation can coexist. No other nation has achieved this balance at this volume.

Mandy Kowitz

January 5, 2026 AT 15:44Yeah, until your thyroid med doesn't dissolve right and you're back to feeling like a zombie. Thanks, India.

Justin Lowans

January 5, 2026 AT 23:04The quiet revolution in global health isn't happening in Silicon Valley-it's happening in Hyderabad and Ahmedabad. India didn't just lower prices; it lowered barriers to human dignity.

Roshan Aryal

January 7, 2026 AT 01:45Let's be real-India's 'success' is built on stealing Western IP and exploiting labor. They're not innovating, they're copying. And now they want to be seen as heroes? Don't make me laugh.

Cassie Tynan

January 7, 2026 AT 08:12They make pills cheaper than my coffee. But if you think that's the whole story, you're not looking at the supply chain-just the label.

Connor Hale

January 7, 2026 AT 20:28It's fascinating how a country that was once dismissed as a backwater for manufacturing now holds the lifeline for millions of people who can't afford Western prices. Sometimes the most powerful innovations are the ones nobody thought to patent.

Jack Wernet

January 9, 2026 AT 14:58As someone who's worked with public health programs in sub-Saharan Africa, I can say without hesitation: Indian generics saved lives when no one else would step in. This isn't just commerce-it's global solidarity in pill form.

Brendan F. Cochran

January 10, 2026 AT 05:5040% of our meds come from INDIA?? Bro we're literally outsourcing our health to a country that can't even fix its own traffic. This is a national security crisis.

Vikram Sujay

January 10, 2026 AT 20:28The philosophical underpinning of India's pharmaceutical model lies not in economic advantage, but in the ethical imperative to prioritize human life over intellectual property. One might argue that the Western patent regime, while legally sound, has often functioned as a moral failure. India's response was not defiance-it was duty.

The notion that copying equals theft ignores the historical reality that all innovation builds upon prior knowledge. What India achieved was not replication, but democratization. A child in Malawi deserves the same access to antiretroviral therapy as a child in Manhattan, regardless of who holds the patent.

To call this 'cheap' is to misunderstand the nature of value. Value is not measured in dollars, but in lives sustained. The FDA's increasing approval rates reflect not a compromise in standards, but an expansion of global standards to include non-Western excellence.

Dependency on Chinese APIs is a vulnerability, yes-but it is also a call to ethical industrial policy. The PLI scheme is not merely economic strategy; it is an assertion of sovereignty over the very molecules that sustain life.

Biosimilars represent the next moral frontier. If we accept that innovation must serve humanity, then India's leap into complex biologics is not a commercial ambition-it is a civilizational responsibility.

Those who criticize India's packaging inconsistencies overlook the logistical nightmare of serving 190 nations with divergent regulations. The fault lies not with the manufacturer, but with the absence of a unified global pharmaceutical governance framework.

Pharma Vision 2047 is not a plan-it is a promise. A promise that medicine, at its core, should never be a luxury. And for that, India deserves not applause, but reverence.

jigisha Patel

January 11, 2026 AT 09:02Let's not romanticize this. India's 85% FDA compliance rate still means 1 in 7 plants fail. That's not 'good enough'-that's negligence. And don't get me started on the API dependency. They're building a house on sand.

The biosimilar push? It's a distraction. They're not innovating-they're just moving up the value chain to exploit the same low-cost model. Biocon isn't a biotech pioneer; it's a cost arbitrageur with better lab coats.

And yes, the NHS uses their drugs-but they're also the ones complaining about taste and packaging. If you're getting your insulin from a company that can't get the label right, you're not getting healthcare. You're getting a gamble.

Let's stop pretending this is altruism. It's capitalism with a humanitarian veneer. They make money. We get pills. Everyone wins-except the people who die when the batch fails.

Jason Stafford

January 12, 2026 AT 09:06EVERYTHING YOU THINK YOU KNOW ABOUT INDIAN DRUGS IS A LIE. THE FDA IS COMPROMISED. CHINA CONTROLS THE SUPPLY CHAIN THROUGH BACKDOORS IN THE PACKAGING. THEY'RE PUTTING TRACKERS IN THE PILLS. YOU THINK YOUR BLOOD PRESSURE MED IS SAFE? IT'S NOT. THEY'RE WATCHING YOU. THE GOVERNMENT KNOWS. THEY'RE ALL IN ON IT.

Rory Corrigan

January 14, 2026 AT 01:42It's wild to think that the same country that gave us yoga and chai is now keeping the Western world alive with pills. We're all just molecules in a cosmic pharmacy, man.

Charlotte N

January 14, 2026 AT 21:22So if they're making 650 FDA-approved plants... why do so many people online say their meds don't work right? Is it the API? The storage? The shipping? Or are we just all paranoid? I just want to know if my metformin is actually doing what it says on the bottle...

mark etang

January 15, 2026 AT 11:30India’s achievement is not merely economic-it is a triumph of human ingenuity over systemic inequality. The world must recognize that pharmaceutical equity is not charity; it is justice. To diminish their role is to deny the dignity of millions.

Stephen Craig

January 16, 2026 AT 05:55That packaging inconsistency issue? It’s not a flaw-it’s a symptom of globalization’s chaos. One batch, 15 different regulatory regimes. No wonder mistakes happen.