How to Understand Boxed Warning Label Changes Over Time

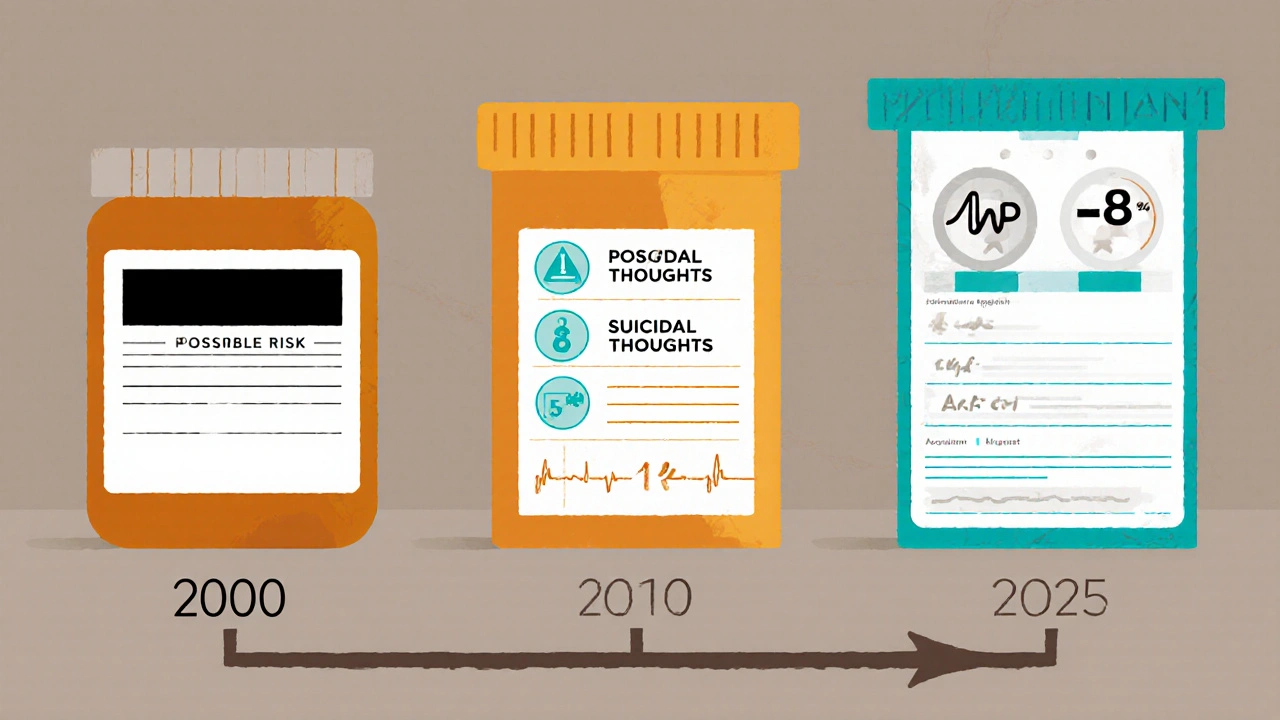

When you pick up a prescription, you might not notice the small black border at the top of the drug’s prescribing information. But that box? It’s one of the most important safety tools in modern medicine. Known as a boxed warning-or sometimes a black box warning-it’s the FDA’s strongest alert for a drug’s most dangerous risks. These aren’t just reminders. They’re life-or-death signals: things like sudden heart failure, suicidal behavior, liver failure, or death from rare side effects. And these warnings don’t stay the same. They change. Sometimes they get stronger. Sometimes they get removed. Sometimes they become more precise. Understanding how and why these changes happen can help you make smarter decisions about your meds-or those of a loved one.

What Exactly Is a Boxed Warning?

A boxed warning is a mandatory safety alert required by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for certain prescription drugs. It appears as a bordered section-traditionally black, though digital formats now allow other colors-at the very beginning of the official prescribing information. This isn’t a footnote. It’s front-and-center because the risks it describes can cause death or serious hospitalization.

These warnings aren’t added lightly. The FDA only uses them when there’s clear evidence of a risk so severe that it changes how a drug should be used. For example, a boxed warning might say: "This drug can cause severe liver damage. Do not use if you have a history of liver disease." Or: "Increased risk of suicidal thoughts in patients under 25. Monitor closely during first months of treatment."

Since 1979, when the FDA first introduced this system, boxed warnings have become a cornerstone of drug safety. About one-third of all major safety actions taken by the FDA since 2000 have involved adding, updating, or removing a boxed warning. In fact, drugs approved after 1992 are more than twice as likely to get a boxed warning later on-partly because approval pathways got faster, and safety data had to be gathered after the drug hit the market.

Why Do Boxed Warnings Change?

Drugs aren’t fully understood the day they’re approved. Clinical trials involve thousands of patients, but real-world use involves millions. That’s where the real risks show up.

Boxed warnings change for three main reasons:

- New safety data: A rare side effect shows up in 1 in 10,000 patients after the drug’s been used for years. The FDA reviews reports from doctors, patients, and hospitals through its MedWatch system-over 1.2 million reports come in every year.

- Better science: Early warnings were vague. Today’s are specific. For example, the 2004 warning for antidepressants in young people just said "increased risk of suicidal thinking." By 2006, it was updated to name the exact age group (18-24) and added clear instructions: "Monitor for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual behavior."

- Re-evaluation: Sometimes, new studies prove a warning was wrong. In 2016, the FDA removed the boxed warning for Chantix (varenicline), which had linked the smoking cessation drug to depression and suicidal thoughts. A massive 8,144-person study found no increased risk compared to placebo. The warning came down.

Changes aren’t always about danger. Sometimes, they’re about clarity. In 2017, the warning for Unituxin (dinutuximab) replaced the word "neuropathy" with "neurotoxicity"-a more accurate term for how the drug damages nerves. It also added exact criteria for stopping treatment: "Discontinue if you have severe unresponsive pain, severe sensory neuropathy, or moderate to severe motor neuropathy."

How to Track Changes Over Time

Keeping up with these changes isn’t easy-but it’s possible. You don’t need to be a doctor. Here’s how to follow updates:

- Use the FDA’s Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database. This official tool tracks every boxed warning update since January 2016. You can search by drug name, date, or type of change. It’s free, public, and updated every quarter. The April-June 2025 update, for example, revised Clozaril’s warning to include myocarditis risk: "0.84 cases per 1,000 patient-years versus 0.12 in other antipsychotics."

- Check Drugs@FDA. This database shows the full history of a drug’s approval and labeling changes. Look at the "Labeling" section to see how warnings evolved since the drug first came out.

- Subscribe to FDA updates. The FDA sends out alerts through MedWatch. You can sign up for email notifications on safety changes.

- Look at professional journals. The American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy publishes quarterly summaries of labeling changes. The April-June 2025 issue listed 17 boxed warning updates across 14 drugs.

For older changes (before 2016), use the MedWatch Medical Product Safety Information archive. It’s not as easy to search, but it’s the only place to find warnings from the 1990s and early 2000s.

Real Examples That Changed the Game

Some warnings didn’t just change-they reshaped how we use drugs.

- Avandia (rosiglitazone): In 2007, a boxed warning was added for heart attack risk in patients with existing heart disease. The warning didn’t pull the drug off the market, but it forced doctors to screen for heart problems first. Studies later showed heart attack rates dropped by 23% in high-risk patients because of this change.

- Depo-Provera: The 2004 warning about bone density loss remains active today. It’s one of the longest-standing warnings and includes precise language: "The degree of loss appears to increase with duration of use and is partially reversible after stopping." That specificity helps doctors decide whether to prescribe it for long-term birth control.

- Clozaril (clozapine): This schizophrenia drug has had multiple updates. The original warning was about agranulocytosis-a dangerous drop in white blood cells. That’s why patients need monthly blood tests. In 2025, a new addition specified myocarditis risk in the first four weeks of treatment. Now, doctors must check heart enzymes before and after starting the drug.

These aren’t abstract rules. They change what happens in a doctor’s office. For Clozaril, the 2025 update means a patient might get an ECG and blood test before their first dose-not just a week later.

Why Do Doctors Sometimes Miss These Changes?

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: even though boxed warnings are meant to protect patients, many doctors don’t use them well.

A 2017 study found only 43.6% of primary care doctors could correctly identify which drugs had boxed warnings during a real patient visit. Family doctors were even less likely to spot them-76% said they got confused. Why? Too many warnings. Too many drugs. Too little time.

And it’s not just forgetfulness. Some warnings are too vague. A warning about "possible liver damage" doesn’t tell you how often it happens, who’s at risk, or what to do. But a warning that says, "Risk is 1 in 500 for patients over 65 with hepatitis B. Check liver enzymes monthly for 6 months"? That’s actionable.

Surprisingly, warnings about rare but deadly side effects-like liver failure or blood disorders-get followed 78% of the time. Warnings about common but less severe issues, like nausea or dizziness, get ignored 58% of the time. That’s called "warning fatigue." When everything looks dangerous, nothing stands out.

What’s Next for Boxed Warnings?

The system is evolving. The FDA’s 2025-2027 plan aims to make warnings faster, smarter, and more precise.

Right now, it takes 18 to 24 months after a safety signal appears for a warning to be updated. That’s too slow. New pilot programs are testing real-time updates using electronic health records. If a patient on a certain drug ends up in the ER with liver failure, that data could trigger an automatic alert to the FDA-and possibly a warning update within weeks, not years.

Industry analysts predict that by 2030, 40-45% of all prescription drugs will carry a boxed warning-up from 32% in 2020. That’s because:

- More drugs are approved through fast-track programs, which require more post-market monitoring.

- Real-world data collection is getting better. AI can now spot patterns in millions of patient records that human reviewers might miss.

- Patients are more informed. They ask questions. They look up warnings. Doctors can’t ignore them anymore.

But the goal isn’t to add more warnings. It’s to make them matter. The FDA is testing shorter, clearer warnings with specific numbers: "Risk of heart failure: 2.3% in patients over 70," not "may cause heart problems."

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a researcher to use boxed warnings wisely. Here’s how to protect yourself:

- Ask your doctor: "Does this drug have a boxed warning? When was it last updated?" Don’t be shy. It’s your health.

- Check the label. Most drug packaging now includes a QR code that links to the full prescribing information. Scan it. Read the first section.

- Keep a medication list. Include the drug name, dose, and any boxed warning you’ve been told about. Bring it to every appointment.

- Report side effects. If you have a bad reaction, report it to MedWatch. It’s anonymous. It matters.

Boxed warnings aren’t meant to scare you off a drug. They’re meant to help you use it safely. The best warnings don’t say "Don’t take this." They say, "Take this, but here’s how to stay safe."

What does a boxed warning mean for my prescription?

A boxed warning means the drug has a serious, potentially life-threatening risk that requires special attention. It doesn’t mean you can’t take it-it means you and your doctor need to be extra careful. This might mean more frequent blood tests, avoiding certain other drugs, or monitoring for specific symptoms. Always ask your doctor what the warning means for your situation.

Can a boxed warning be removed?

Yes. If new studies show the risk is lower than originally thought-or if the warning was based on flawed data-the FDA can remove it. The most famous example is Chantix, which had a boxed warning for suicidal thoughts from 2009 until 2016. After a large clinical trial found no increased risk, the FDA took it down. Removal is rare, but it happens.

Why do some warnings get updated instead of removed?

Updates happen when the science gets more precise. Early warnings were broad: "May cause liver damage." Today’s warnings say: "Risk is 1 in 200 for patients with hepatitis C, especially if over 50. Check ALT levels monthly for the first 6 months." Updates add detail, not just remove risk. They help doctors make better decisions.

How often are boxed warnings updated?

On average, the FDA issues 25-30 new or updated boxed warnings each year. Since 2015, the pace has increased. In the first half of 2025 alone, there were 17 updates to existing warnings. The most common triggers are new safety reports from the public, studies published in medical journals, or data from electronic health records.

Are boxed warnings the same in other countries?

No. The U.S. uses boxed warnings, but other countries have different systems. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) uses "contraindications" and "warnings" in their product information, but they don’t use a formal boxed format. Canada and Australia have similar alert systems, but the wording and strength of alerts can vary. Always check the prescribing information for your country’s regulatory agency if you’re taking a drug outside the U.S.

ASHISH TURAN

November 15, 2025 AT 10:33Had no idea boxed warnings were this dynamic. I just assumed they were static red flags. Learning that Chantix had one removed after a big study? That’s huge. Makes me want to check my own meds now.

Ryan Airey

November 16, 2025 AT 13:02Stop pretending the FDA gives a damn about patients. These warnings get updated only when lawsuits pile up or a drug’s stock crashes. That Clozaril myocarditis update? Came after three dead 19-year-olds in Texas. The system’s broken, and they’re just cleaning up the mess after the fact.

Hollis Hollywood

November 17, 2025 AT 22:13I’ve been on Depo-Provera for six years, and I read that warning every time I get the shot. It says bone density loss is "partially reversible"-but nobody tells you what that actually means. Is it 30%? 70%? I asked my OB-GYN last month and she just shrugged. That’s the problem. These warnings are written like legal contracts, not health advice. We need plain language, not jargon. I don’t need to know "degree of loss increases with duration," I need to know if I’ll be able to walk at 50.

And honestly? The fact that doctors miss 56% of these warnings? That’s terrifying. I’m not blaming them-they’re drowning in paperwork-but someone needs to build a simple app that pops up the current warning when you scan a prescription barcode. Like a QR code that says, "This drug can kill you if you’re over 65 and on statins. Here’s what to watch for."

Aidan McCord-Amasis

November 18, 2025 AT 07:17Boxed warning? More like boxed BS. 🤡

Chris Bryan

November 18, 2025 AT 16:51Who funded that "8,144-person study" that cleared Chantix? Big Pharma? Of course they did. The FDA’s been in bed with pharmaceutical giants since 2002. They removed the warning because they needed to keep sales up-not because it was safe. And now they’re pushing "real-time updates"? That’s just a front for mandatory EHR surveillance. They’re tracking your every heartbeat, every ER visit, to predict what drug you’ll be prescribed next. Welcome to the medical surveillance state.

Jonathan Dobey

November 19, 2025 AT 21:42Boxed warnings are the last flickering candle in the cathedral of pharmaceutical nihilism. We’ve outsourced our moral agency to regulatory bureaucracies that operate on delayed feedback loops and statistical ghosts. The warning isn’t about risk-it’s about the epistemological collapse of trust. When a drug’s label evolves from "may cause liver damage" to "1 in 200 risk for hepatitis C-positive patients over 50," we’re not getting clarity-we’re getting the illusion of precision. The math is a narcotic. It sedates us into believing that numbers can contain chaos. But the body doesn’t care about p-values. It only knows pain, and silence, and the hollow echo of a doctor saying, "I didn’t know."

Adam Dille

November 20, 2025 AT 14:14Love that you included how to track updates. I just scanned the QR code on my new blood pressure med and it linked straight to the FDA label with the boxed warning highlighted. Super easy. Also, I reported my weird dizziness last week via MedWatch-got an auto-reply saying "your report is valuable." Felt good to do something small. 🙌

Katie Baker

November 21, 2025 AT 02:22My grandma’s on Clozaril and I just showed her the 2025 update about myocarditis. She was scared, but then we called her cardiologist and he said they already tested her heart enzymes before starting. She felt way better knowing they were watching. Thanks for the practical tips-I’m printing this out for my mom’s next appointment.

John Foster

November 22, 2025 AT 03:11There is a quiet horror in the way modern medicine treats the human body-as if it were a machine that can be debugged with a new label. We have become so obsessed with the architecture of risk that we forget the soul of care. The boxed warning is not a safeguard-it is a monument to our collective failure to understand the body before we poison it. We rush drugs to market, then scramble to write warnings as if the body’s screams were merely administrative inconveniences. And now we speak of "real-time updates" as if data streams can replace compassion. But no algorithm can feel the trembling hand of a patient who just learned their medication might stop their heart. The real crisis isn’t in the warning. It’s in the silence between the lines.

Edward Ward

November 23, 2025 AT 13:09Just wanted to add-I’ve been using the FDA’s SrLC database since 2023, and it’s been a game-changer. I’m a pharmacist, and I used to rely on drug reps or email alerts, which were always late. Now I check it every Monday morning. Last month, I caught an update to Lamotrigine’s warning about Stevens-Johnson syndrome in pediatric patients-no one else in my clinic had seen it yet. I emailed the whole team. Also, I’ve started keeping a running Google Doc of all boxed warnings for my patients’ meds. I print it and give them a copy. It’s not glamorous, but it saves lives. And yes, I over-punctuate. Sue me.

Andrew Eppich

November 23, 2025 AT 16:48The notion that patients should independently verify drug warnings is fundamentally irresponsible. The prescribing physician is the trained professional. The patient is not. Expecting laypersons to interpret MedWatch data or parse FDA labeling is a dereliction of duty by the medical establishment. This article, while well-intentioned, promotes dangerous overreach. The boxed warning exists for the physician’s guidance-not the patient’s curiosity.

Jessica Chambers

November 24, 2025 AT 05:55Wow. So the FDA updates warnings… but doctors don’t read them? 🤦♀️ And we wonder why people stop taking meds. At least the QR codes are a step up from the tiny print that used to be on the bottle. Still… I’d rather have a doctor who remembers the warning than a QR code that links to a 40-page PDF.