How to Coordinate Medication Plans After Hospital Discharge: A Step-by-Step Guide for Patients and Providers

When you leave the hospital, your body is still healing-but your medication plan might be completely different from what you were taking at home. That’s not a mistake. It’s common. But if no one checks to make sure those changes are safe, clear, and followed, you’re at serious risk. About one in three patients get hit with a medication error in the first 30 days after leaving the hospital. Some pills get dropped. Others get doubled. New ones are added without explaining why. And too often, no one ever asks if you’re actually taking them.

This isn’t about blame. It’s about coordination. Medication reconciliation after discharge isn’t optional. It’s a nationally recognized safety standard (NQF 0097), required by Medicare and Medicaid, and backed by data showing it cuts readmissions by nearly 30%. But it only works if everyone-patient, doctor, pharmacist, family-plays their part.

What Exactly Is Medication Reconciliation?

Medication reconciliation means comparing what you were taking before you went to the hospital with what you’re supposed to take when you leave. It’s not just writing down a list. It’s asking: Did they stop your blood pressure pill? Why? Should it be restarted? Did they add a new painkiller? Is it safe with your heart medicine? Are you even taking your diabetes meds at home?

The goal? Catch mismatches before they hurt you. Studies show that 30-70% of patients have at least one error in their discharge meds. These aren’t small slips. They’re dangerous. One patient had their anticoagulant stopped in the hospital for surgery-and never restarted. Three weeks later, they had a stroke. Another was given a new antibiotic that interacted with their cholesterol drug, causing severe muscle damage.

The process isn’t magic. It’s methodical. The National Quality Forum and CMS require providers to document one of seven specific actions: comparing your current meds with discharge meds, noting that meds were reviewed, or showing proof that reconciliation happened during a follow-up visit. But documentation alone doesn’t fix the problem. Action does.

Who Should Be Doing This?

Too many people think the doctor handles it. But the truth? The best outcomes come from pharmacists.

A 2023 study across multiple hospitals found that when pharmacists led the reconciliation process, medication errors dropped by 32.7%. Readmissions fell by 28.3%. Why? Pharmacists don’t just know drugs-they know how they interact, how patients actually use them, and what gaps exist in care.

Doctors are busy. Nurses are stretched thin. But pharmacists specialize in this. They can spend 20 minutes on the phone with you, checking if you filled your new prescriptions, if you’re confused about dosing, or if you’re still taking that old painkiller your doctor forgot to cancel.

That’s why top-performing hospitals now embed pharmacists in discharge teams. They sit with you before you leave. They review your list. They call your primary care doctor. They even follow up within 48 hours. And they bill for it-through CPT codes 99495 and 99496, which pay for transitional care visits. But here’s the catch: only one provider can bill for that visit per discharge. So if your PCP and your cardiologist both try to do it? Only one gets paid. That creates tension. And gaps.

How to Make Sure Your Meds Are Right Before You Leave

You don’t have to wait for someone else to fix this. Here’s what you can do before you walk out the door:

- Bring your own list. Don’t rely on memory. Write down every pill, patch, cream, vitamin, supplement, and herbal tea you take at home. Include doses and times. Even the ones you only take when you feel bad.

- Ask for a printed copy. Before discharge, ask: “Can I get a copy of my updated medication list?” Don’t settle for “We’ll send it to your doctor.” Get it in your hands.

- Check for changes. Compare your list to the one they give you. Did they stop your insulin? Add a new anticoagulant? Change the dose of your thyroid pill? If something’s different, ask: “Why? Is this permanent? Should I stop taking my old one?”

- Ask about timing. “When do I start this new pill?” “Do I take it with food?” “What if I miss a dose?” Don’t assume. Ask.

- Confirm refills. “Are these prescriptions ready at my pharmacy?” “Do I need to call in for refills?”

One patient left the hospital with a new blood thinner but no prescription. She didn’t know until she got home and tried to fill it. She missed two days. Two days later, she had a blood clot.

What Happens After You Get Home?

Leaving the hospital is just the start. The real danger zone is the first 30 days.

Thirty-five to fifty percent of patients don’t take their meds as prescribed after discharge. Why? Confusion. Cost. Side effects. Lack of follow-up. Or worse-no one checked if they understood.

That’s why follow-up isn’t optional. It’s life-saving.

Here’s what a strong post-discharge plan looks like:

- Call within 48 hours. A pharmacist or nurse calls to ask: “Did you fill your scripts? Are you having side effects? Do you know why you’re taking each pill?”

- Follow-up visit within 7 days. Your PCP or pharmacist reviews your meds in person. They check your EHR, compare it to your home list, and update everything.

- Use tech. Apps like Medisafe or MyTherapy let you log your meds and get reminders. Top hospitals now give these to patients at discharge.

- Involve your caregiver. If you live alone or have memory issues, have someone else sit with you during the reconciliation. They can take notes. They can ask questions you forget.

One man with heart failure was discharged with six new meds. He didn’t understand any of them. His daughter, who lived 200 miles away, got a call from the hospital’s pharmacist three days later. She came home, sat with him, and figured out which pills were which. He didn’t go back to the hospital.

What If Your Doctor Doesn’t Do This?

Not every provider has the time, training, or system to do this well. If you’re not getting a clear medication list, or no one calls you after discharge, here’s what to do:

- Call your primary care provider’s office within 24 hours of discharge. Say: “I was just discharged from the hospital. I need my meds reconciled. Can you schedule a follow-up?”

- If they say no, ask: “Can you refer me to a pharmacist who does medication therapy management?” Medicare and many private insurers cover this.

- Go to a community pharmacy. Many now offer free post-discharge med reviews. Ask for the pharmacist. Don’t just ask the technician.

- Use your EHR portal. Log in. Download your discharge summary. Compare it to your home list. Flag anything that doesn’t match. Send a secure message to your doctor.

You don’t need permission to protect yourself. You just need to ask.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In 2026, Medicare will penalize doctors who don’t report medication reconciliation. Hospitals face financial penalties if patients come back because of a medication error. That’s why more than 75% of hospitals will have pharmacist-led reconciliation programs by the end of this year.

But technology alone won’t fix this. AI can flag possible errors in your chart. But it can’t ask you if you’re still taking that old blood pressure pill because you think it makes you feel better. It can’t hear the hesitation in your voice when you say, “I can’t afford this.”

Real reconciliation happens when a human listens. When someone checks in. When you’re not just a discharge summary-you’re a person.

The data is clear: medication reconciliation saves lives. It cuts readmissions. It reduces ER visits. It gives you control.

Don’t wait for the system to catch up. Be the one who asks. Be the one who calls. Be the one who holds the list.

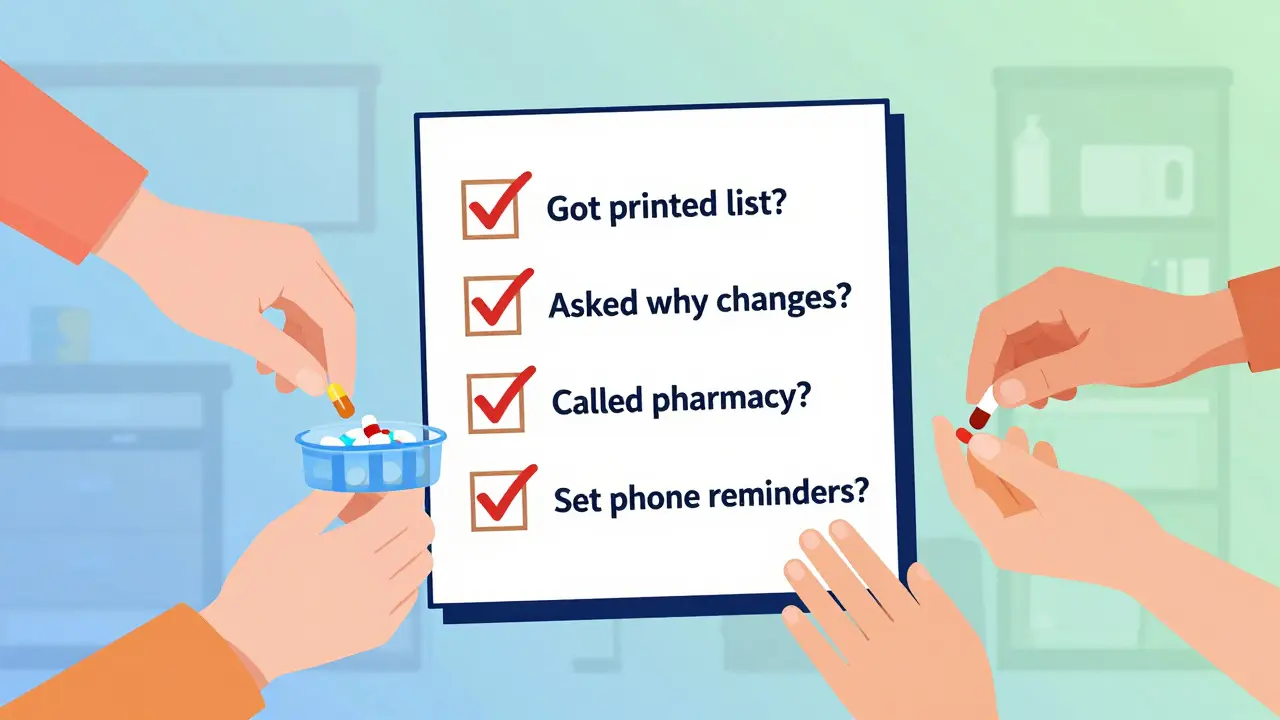

Quick Checklist: Your Post-Discharge Med Plan

- ✅ Got a printed, updated medication list before leaving the hospital?

- ✅ Compared it to your home list? Noted any changes?

- ✅ Asked why each change was made?

- ✅ Confirmed all prescriptions are filled and ready?

- ✅ Scheduled a follow-up with your PCP or pharmacist within 7 days?

- ✅ Had someone else (family, friend) review the list with you?

- ✅ Set up pill reminders on your phone or app?

- ✅ Called your pharmacy or provider if anything doesn’t make sense?

If you answered “no” to any of these, take action today. One call could keep you out of the hospital.

What happens if I don’t get my meds reconciled after hospital discharge?

Without medication reconciliation, you’re at high risk for dangerous errors-like taking a drug that interacts with a new one, missing a critical medication, or doubling up on doses. Studies show 30-70% of patients have at least one mistake in their discharge meds. These errors cause up to 50% of post-discharge medication problems and are linked to 6.5% of all hospital readmissions. In some cases, they lead to emergency visits, organ damage, or death.

Can my primary care doctor and specialist both bill for medication reconciliation after my discharge?

No. Medicare and private insurers only allow one provider to bill for a transitional care visit (CPT 99495 or 99496) per discharge. If both your PCP and cardiologist try to bill, only one will get paid. This creates confusion and sometimes delays. That’s why it’s best to assign one provider to lead the reconciliation-usually your PCP or a pharmacist. If you’re unsure who should do it, ask your discharge coordinator or call your insurance.

Do I need to go to the doctor’s office for medication reconciliation?

No. You don’t need an in-person visit. Medication reconciliation can be done over the phone, via video call, or even through secure messaging in your patient portal. The CPT II code 1111F allows providers to document reconciliation without a visit. Many pharmacies and telehealth services now offer free post-discharge med reviews. The key isn’t the location-it’s that the reconciliation happens and is documented within 30 days.

What if I can’t afford my new prescriptions after discharge?

Cost is one of the top reasons people skip meds after discharge. If you can’t afford your new prescriptions, tell your doctor or pharmacist immediately. They can often switch you to a generic, apply for patient assistance programs, or connect you with nonprofit help. Some hospitals have social workers who help with medication costs. Never stop a medication because of cost-ask for help first.

How do I know if my meds were properly reconciled?

You’ll know if your provider can show you a side-by-side comparison of your home meds and discharge meds, explain why changes were made, and confirm you understand how and when to take each one. Ask: “Can you show me what was changed and why?” If they can’t, the process wasn’t done right. You have the right to a clear, written list with explanations.

If you’ve just been discharged, don’t wait for someone else to fix your meds. Take the list. Make the call. Ask the questions. Your health depends on it.

Dave Old-Wolf

January 9, 2026 AT 07:54Ken Porter

January 9, 2026 AT 17:15Luke Crump

January 10, 2026 AT 18:52Aubrey Mallory

January 10, 2026 AT 22:53Molly Silvernale

January 12, 2026 AT 08:23Kristina Felixita

January 13, 2026 AT 17:41Joanna Brancewicz

January 14, 2026 AT 01:27Lois Li

January 15, 2026 AT 16:27christy lianto

January 15, 2026 AT 20:23swati Thounaojam

January 16, 2026 AT 05:55Annette Robinson

January 17, 2026 AT 21:02Manish Kumar

January 18, 2026 AT 14:49