How Advertising Shapes Perceptions of Generic Drugs

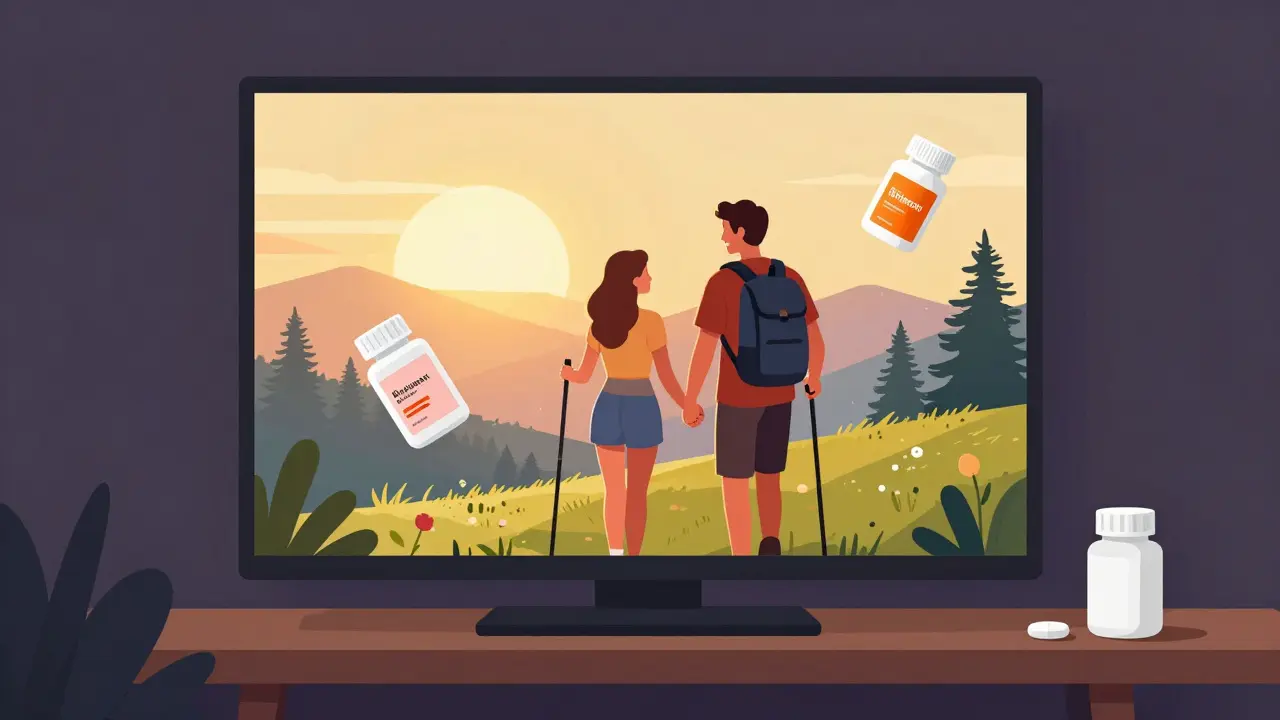

When you see a TV ad for a new cholesterol drug with a serene couple hiking at sunrise, it’s easy to think that’s the best option for your health. But what you don’t see is the cheaper, equally effective version sitting on the pharmacy shelf-generic-with no fancy jingle, no scenic backdrop, no celebrity doctor. And that’s not an accident.

Ads Don’t Just Sell Drugs-They Shape Beliefs

In the U.S., pharmaceutical companies spent over $6.5 billion on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising in 2020. That’s more than ten times what they spent in 1996. These ads don’t just inform-they persuade. And they do it in ways that make branded drugs feel superior, even when the science says otherwise.Generic drugs contain the exact same active ingredients as their branded counterparts. They’re held to the same FDA standards. They work the same way. But because they’re not advertised, most people don’t know that. When patients hear a drug name repeatedly on TV, they start to believe it’s newer, safer, or more advanced. That belief sticks-even when their doctor suggests a generic alternative.

The Spillover Effect: Ads Boost Generics, But Not the Way You Think

Here’s the twist: advertising for branded drugs like Lipitor or Humira doesn’t just increase sales of those specific pills. It also increases prescriptions for other drugs in the same class, including generics. That’s called the spillover effect. A patient sees an ad for a branded statin, asks their doctor for it, and ends up getting a generic version because it’s cheaper and covered by insurance.So, does advertising help generics? Technically, yes-but not because people want them. It’s because the system forces a substitution. The patient didn’t choose the generic. They chose the drug class. The generic won by default, not by appeal.

And here’s the problem: when patients are motivated by ads, they’re less likely to stick with their medication. Research from the Wharton School shows that people who start a new drug because of an ad have lower adherence rates than those who begin treatment based on a doctor’s recommendation. The ad created excitement, not understanding. And without understanding, compliance drops.

Doctors Are Caught in the Middle

A 2005 JAMA study tested this by having actors play patients and request specific drugs during simulated doctor visits. When patients asked for a branded antidepressant shown in ads, doctors prescribed it 80% of the time-even when the patient didn’t meet clinical criteria for that drug. When no request was made, prescriptions dropped to 20%.Fast-forward to today: a University of Montana study found that physicians filled 69% of patient requests for advertised drugs they considered inappropriate. That’s not patient empowerment. That’s marketing overriding clinical judgment.

Doctors know generics are just as effective. But when a patient walks in saying, “I saw this on TV,” it’s easier to write the script than to explain why the cheaper option is just as good. The ad did the hard part-created the demand. The doctor just has to meet it.

Why Generics Don’t Get Ads (And Why That Matters)

Generic manufacturers don’t advertise. Why? Because they can’t afford to. Brand-name companies spend millions on TV, digital, and print ads to build loyalty. Generics? They rely on price and availability. There’s no emotional hook. No smiling families. No voiceover saying, “This could be your new beginning.”Instead, generic ads-if they exist-are clinical, dry, and buried in small print. They list side effects, not benefits. They don’t tell you how life could change. They just say, “This is the same as Brand X, but cheaper.” And in a world saturated with polished, emotionally charged messaging, that’s not enough.

The result? Generics are seen as second-rate. Not because they are. But because they’re invisible in the marketplace of ideas.

Ads Distort Risk and Benefit

FDA research from 2018 found that even after seeing an ad four times, most people still didn’t remember the risks. Benefit information stuck better-but only slightly. Risk details? They faded fast.That’s intentional. Ads are designed to make you feel something, not think critically. You see a person dancing with their grandchild after starting a new medication. You don’t see the fine print about liver damage or the 1 in 50 chance of severe side effects.

Generics don’t get this treatment. Their safety profile is identical-but without the emotional story, they’re overlooked. People don’t fear generics. They just don’t think about them at all.

The Cost of Perception

Every dollar spent on DTC advertising returns more than $4 in sales. That’s a massive incentive for drugmakers to keep advertising. But it comes at a cost: higher prices, more unnecessary prescriptions, and a public that believes branded equals better.The U.S. spends more on prescription drugs than any other country. Part of that is because we’re buying what we see on TV-not what we need. Generics can cut drug costs by 80% or more. Yet, in 2020, only 90% of prescriptions filled were generics-not because patients chose them, but because insurance pushed them.

When patients are educated by ads, not doctors, they’re more likely to ask for the most expensive option. And when doctors give in, the system pays the price.

What Could Change?

There’s no easy fix. But here’s one idea: require ads for branded drugs to include a clear, visible mention of available generic alternatives-same active ingredient, same effectiveness, lower cost. No fine print. No small font. Just a simple statement: “A generic version of this drug is available and covered by most insurance plans.”Some countries already do this. In Canada and the U.K., DTC ads for prescription drugs are banned. But even in the U.S., we could demand better. If ads are going to be allowed, they should be fair. Not just persuasive.

Patients deserve to know that a $4 generic pill can do the same job as a $120 branded one. And if they still want the brand? That’s their choice. But that choice should be informed-not manufactured by a 30-second commercial with a sunset and a dog.

Alex Danner

January 7, 2026 AT 07:44Let me tell you something-I used to think brand-name meds were superior until my insurance forced me onto a generic for my blood pressure. Same pill. Same results. No more dizziness. And I saved $110 a month. The only difference? No sunset. No dog. No voiceover telling me I’m ‘ready for my best life.’ Just a little white tablet that works like a charm.

Ad agencies aren’t selling medicine. They’re selling hope. And hope doesn’t come cheap.

Elen Pihlap

January 8, 2026 AT 20:45i just saw an ad for that one drug with the dog and i cried lol i need it so bad

Sai Ganesh

January 9, 2026 AT 13:26In India, generics are the norm. We don’t have luxury of branded drugs for most. But here’s the irony-when Indians go to the U.S. for treatment, they’re shocked that people pay $120 for a pill that costs $4 back home. The ad machine doesn’t just distort perception-it exploits economic disparity.

It’s not about science. It’s about who gets to tell the story.

Paul Mason

January 10, 2026 AT 14:40Look, I’m British and we don’t get this crap on TV here. No ads for pills. Doctors decide. Patients trust them. Result? Lower costs, better outcomes. Why can’t America just be sensible?

It’s like buying a car because you saw a guy in a suit driving it on a beach. You don’t care if it’s a Toyota or a Lamborghini-you just want it to get you to work.

Katrina Morris

January 10, 2026 AT 19:36i never realized how much ads affect what we take

my mom swears her brand name one works better but she cant even tell me what its for

maybe its just the name she likes

also i think the commercials make her feel like shes doing something right

not sure if that makes it better or worse

Anthony Capunong

January 11, 2026 AT 04:05America leads the world in innovation and medical breakthroughs. But now we’re letting some corporate ad agency tell us what to take? No. We’re not some third-world country that needs to be sold medicine like it’s a timeshare. We’re the U.S. We can do better than this. Stop the ads. Trust your doctor. Stop being manipulated.

Emma Addison Thomas

January 11, 2026 AT 09:01It’s funny how we treat health like a product. We want the shiny one with the pretty packaging. But when it comes to our bodies, isn’t it the inside that matters?

I think we need more stories about people who saved money and stayed healthy on generics. Not ads with sunsets. Real stories. Quiet ones. The kind that don’t scream but still reach you.

Rachel Steward

January 13, 2026 AT 00:26Let’s be real-the entire pharmaceutical industry is a Ponzi scheme built on placebo branding. The FDA approves generics because they’re identical. The doctors know it. The insurers push them. But the public? They’re kept in the dark because emotion sells better than data.

And the worst part? The people who benefit most from generics-the elderly, the low-income, the uninsured-are the ones least likely to ever see a commercial. They’re the ones paying the price for someone else’s emotional manipulation.

Anastasia Novak

January 13, 2026 AT 22:10Ugh. Of course it’s the ads. Everything in America is about branding now. Even your pain. Even your depression. Even your cholesterol. You don’t have a condition-you have a *lifestyle*. And if you’re not taking the one with the cinematic sunrise and the golden retriever, you’re just not trying hard enough.

Meanwhile, the generic? It’s the quiet kid in the back of the class who aced the test. No one claps. No one notices. But they’re the one who actually showed up.

Jonathan Larson

January 15, 2026 AT 09:31While the systemic issues raised here are profound, I would propose a more constructive path forward: a public health campaign-funded by federal agencies or nonprofit coalitions-that educates patients on the equivalence of generics, using the same emotional storytelling techniques employed by pharmaceutical marketers.

Imagine a commercial featuring an elderly couple, not hiking at sunrise, but gardening together after years of stable health on a $3 generic. No jingle. No celebrity. Just truth. Quiet. Resonant. Human.

Marketing isn’t inherently evil. It’s the absence of ethical storytelling that’s the problem. We have the tools. We just need the will.