Generic Drug Shortages: Causes and How They Limit Patient Access

Every year, millions of Americans rely on generic drugs to manage everything from high blood pressure to diabetes to infections. These medications are cheaper, widely available, and just as effective as their brand-name counterparts. But in recent years, the shelves have been empty more often than not. As of April 2025, there are 270 active drug shortages in the U.S.-and nearly all of them are generic drugs.

Why Are Generic Drugs So Often Out of Stock?

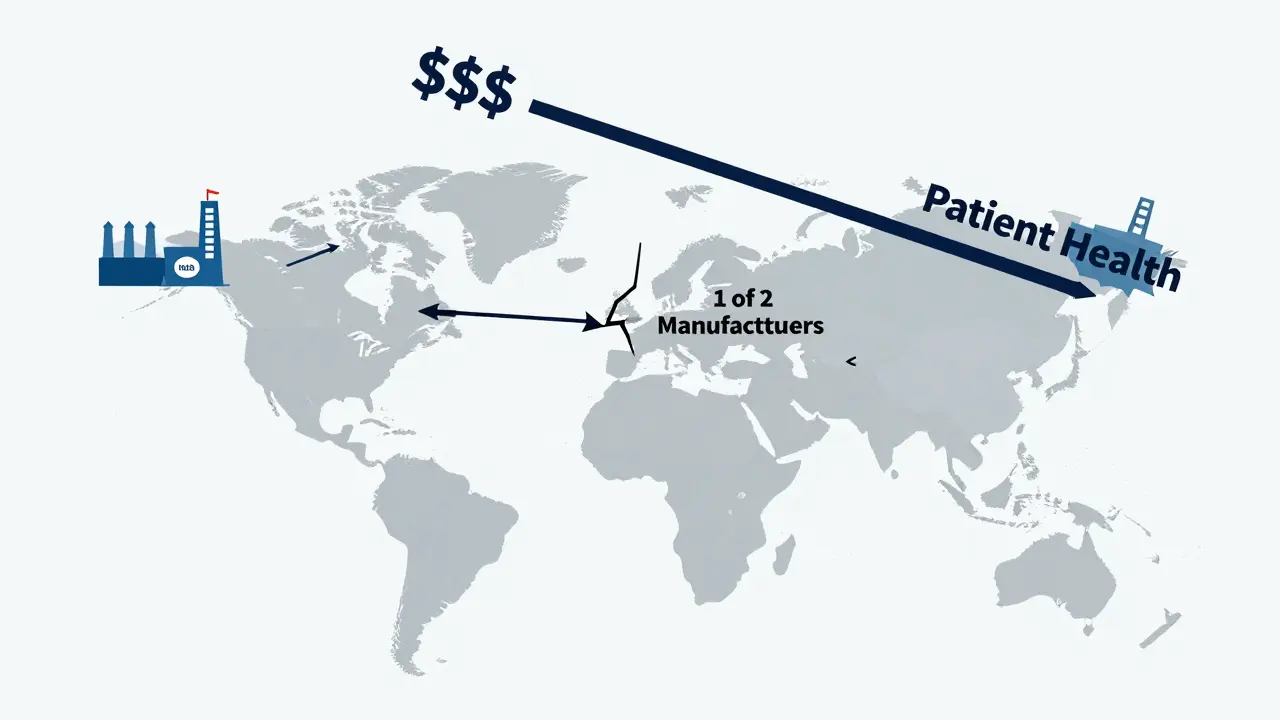

It’s not random. Generic drug shortages happen because the system is built to fail. These drugs make up 90% of prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they earn manufacturers only 5-10% gross profit margins-compared to 30-40% for brand-name drugs. When profit is this thin, companies don’t invest in extra capacity, modern equipment, or quality control. They make just enough to meet demand-and if one factory has a problem, there’s no backup. The FDA reports that 62% of all drug shortages since 2020 were caused by manufacturing and quality issues. That means a single contamination, equipment failure, or inspection violation can knock a drug off the market for months. Sterile injectables-like antibiotics, chemotherapy drugs, and IV fluids-are especially vulnerable. They require clean rooms, complex processes, and strict controls. Only a handful of facilities in the world can make them. And about 70% of these drugs have only one or two approved manufacturers. Then there’s the supply chain. Over 80% of the active ingredients in U.S. drugs come from China and India. A factory shutdown in Hyderabad or a port delay in Shanghai can ripple across the entire system. The median duration of a shortage has doubled since 2011-from 12 months to 24 months. That’s two full years without a critical medication.Who Gets Hurt the Most?

Patients don’t just wait longer for their prescriptions-they get sicker. A 2022 American Medical Association survey found that 63% of pharmacists had seen serious patient harm because of shortages. In hospitals, the impact is even worse. An American Hospital Association survey in 2024 showed that 89% of hospitals had to delay treatments. Cancer centers reported that 67% had to change chemotherapy regimens because drugs like cisplatin or doxorubicin weren’t available. Some patients got less effective drugs. Others got nothing. On Reddit, a hospital pharmacist wrote in June 2025: “We’ve been out of vancomycin powder for 8 months. We’re using alternatives that cost more, work slower, and put patients at higher risk of infection.” Vancomycin is a last-resort antibiotic for life-threatening infections. When it’s gone, doctors have to guess. Even chronic pain patients aren’t safe. One post on the Student Doctor Network described how patients were denied opioid refills-not because they were misusing them, but because the drug wasn’t available. Many ended up in emergency rooms with uncontrolled pain.Why Can’t We Just Switch to Another Drug?

Unlike brand-name drugs, where multiple similar options often exist, generic drugs are frequently the only option. Take sodium bicarbonate, used to treat acidosis in kidney patients. There are no therapeutic alternatives. When it’s out, you can’t substitute it with something else. The same goes for many injectables, sedatives, and emergency medications. Even when alternatives exist, they’re not always better. A 2024 HHS report found that when a generic drug goes short, the price of the substitute often jumps by three times the original shortage’s price increase. One study showed that when the generic version of a common blood pressure pill disappeared, the replacement cost patients $200 more per month. Many just stopped filling their prescriptions. Independent pharmacies reported that 43% of patients abandoned prescriptions because of cost or unavailability. That’s not just inconvenience-it’s preventable hospitalizations, worsening conditions, and longer recovery times.

What’s Happening Behind the Scenes?

Pharmacists are drowning in paperwork. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists found that pharmacy staff now spend 15-20 hours a week managing shortages. That’s not time spent counseling patients or checking for dangerous interactions. It’s time spent calling other pharmacies, switching electronic records, reprogramming automated dispensers, and tracking down obscure alternatives. Hospitals have to maintain separate protocols for at least 10 different drug categories just to handle shortages. That’s dozens of extra steps every time a drug is ordered. And it’s not just pharmacists-nurses, doctors, and administrators are pulled into the scramble. A 2025 report found that 72% of hospitals said drug shortages made their existing staffing shortages worse. The financial toll is real too. The American Hospital Association estimates hospitals spend $213 million a year just managing these disruptions. That’s money that could go toward hiring more staff, upgrading equipment, or expanding care.The Bigger Picture: A Market That Doesn’t Reward Reliability

The generic drug market used to be more competitive. In 2015, the top 10 manufacturers controlled 45% of the market. By 2024, that number jumped to 60%. Fewer companies mean less redundancy. And fewer manufacturers mean fewer factories. The number of FDA-registered generic drug facilities in the U.S. dropped 22% between 2015 and 2024-from 1,842 to 1,437. Profit margins have collapsed too. In 2010, generic manufacturers averaged 35% gross margins. By 2024, that fell to 18%. Why? Because buyers-like Medicare, Medicaid, and big pharmacy chains-keep pushing for the lowest price. The system rewards the cheapest bidder, not the most reliable one. The FDA has issued more quality citations than ever. Between 2020 and 2024, manufacturing violations rose 35%. That’s not because companies are getting sloppier-it’s because they’re cutting corners to survive. One manufacturer told investigators they couldn’t afford to upgrade their sterilization equipment because the price they were paid for the drug wouldn’t cover it.

Is There Any Hope?

There are signs of change. In 2020, the Biden administration created the Essential Medicines List to prioritize critical drugs. From 2020 to 2023, shortages of those essential drugs dropped by 32%. But the progress stalled. By early 2024, shortages hit a record high again. The FDA’s Drug Shortage Task Force has four ideas: diversify manufacturing locations, offer financial incentives for reliable production, adopt advanced manufacturing tech like 3D printing, and build better early-warning systems. But none of these fix the core problem: the market doesn’t pay for reliability. Congressional analysts warn that without changing how generics are priced, shortages will keep rising. The Congressional Budget Office predicts 350 active shortages by the end of 2026-with two-thirds being sterile injectables. Some states are trying. A few have passed laws requiring hospitals to report shortages in real time. Others are creating state-level stockpiles of critical drugs. But these are patches, not solutions.What This Means for You

If you take a generic drug, especially a daily medication like metformin, levothyroxine, or lisinopril, don’t assume it’ll always be there. Talk to your pharmacist. Ask if your drug has been on shortage. Find out what alternatives exist-and what they cost. If you’re on an injectable, ask your doctor if there’s a backup plan. Don’t wait until your prescription runs out. If you’re on a long-term medication, consider keeping a small extra supply-when possible. And if your drug disappears, don’t just accept it. Ask your provider to advocate with the pharmacy or hospital. Contact your state’s health department. Share your story. This isn’t just about pills on a shelf. It’s about whether someone with sepsis gets the right antibiotic in time. Whether a cancer patient can start treatment. Whether a diabetic can avoid a hospital stay. The system is broken. But it’s not inevitable. Change only happens when people demand it.Why are generic drug shortages so common compared to brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs are more commonly in shortage because they have extremely low profit margins-often just 5-10%-compared to 30-40% for brand-name drugs. Manufacturers have little financial incentive to invest in backup production, quality upgrades, or excess inventory. With only one or two companies making most generics, any disruption shuts down the entire supply. Brand-name drugs, while sometimes in short supply, often have multiple manufacturers or therapeutic alternatives that help buffer the impact.

Which types of generic drugs are most likely to be in short supply?

Sterile injectables are the most vulnerable. This includes antibiotics like vancomycin, chemotherapy drugs like cisplatin, IV fluids like saline, and anesthetics. These require complex, sterile manufacturing environments that only a few facilities can provide. They also have razor-thin margins, making them easy to cut from production when costs rise or prices stay flat. Over 60% of all drug shortages involve injectables.

Can I switch to a brand-name drug if the generic is unavailable?

Possibly, but it’s not always practical. Brand-name versions of generics can cost 10 to 100 times more. Insurance often won’t cover them without prior authorization, and even then, you may face high out-of-pocket costs. Some drugs, like sodium bicarbonate or certain emergency injectables, have no brand-name equivalent. Your doctor can help determine if a switch is safe and affordable-but it’s not always possible.

How do drug shortages affect hospital care?

Hospitals face treatment delays, forced protocol changes, and increased risks to patient safety. For example, when chemotherapy drugs are unavailable, oncologists may delay treatment cycles or use less effective alternatives. When antibiotics like vancomycin are out, patients with serious infections get broader-spectrum drugs that increase the risk of resistance or side effects. Pharmacists spend 15-20 hours a week just managing shortages, diverting time from direct patient care. Hospitals also spend an estimated $213 million annually dealing with the fallout.

Are generic drug shortages getting worse?

Yes. After peaking at 323 shortages in early 2024, the number dropped slightly to 270 by April 2025-but that’s still far above historical levels. Before 2008, the U.S. saw fewer than 70 shortages per year. Now, it’s over 250. The median shortage length has doubled to 24 months. Experts warn that without policy changes-like paying manufacturers fairly for reliable production-the number could hit 350 by the end of 2026.

What can patients do when their medication is in short supply?

First, talk to your pharmacist and doctor. Ask if your drug is on the shortage list and what alternatives exist. Don’t stop taking your medication without guidance. If alternatives are too expensive or unavailable, ask your provider to help you file a prior authorization request for a brand-name version. You can also contact your state’s health department or patient advocacy groups. Keeping a small extra supply (if allowed) and staying informed through resources like the FDA’s drug shortage database can help you prepare.

Damario Brown

January 15, 2026 AT 01:32bro the system is literally designed to fail. companies make next to nothing on generics so they cut corners, then when a factory in india has a power outage, we all get screwed. why are we surprised? this isn't a bug, it's a feature.

Clay .Haeber

January 15, 2026 AT 17:40oh wow. a 24-month shortage. how quaint. next you'll tell me we still use fax machines to order insulin. the real tragedy? we're all just waiting for the next person to die so congress remembers we exist.

Priyanka Kumari

January 15, 2026 AT 19:57I’ve seen this firsthand in rural India too-when essential antibiotics vanish, families travel for days just to find a substitute. It’s not just a US problem. We need global supply transparency and fair pricing, not just patchwork fixes.

Avneet Singh

January 16, 2026 AT 02:20the real issue is that we still think capitalism can solve healthcare. you can’t outsource dignity to a balance sheet. this isn’t about manufacturing-it’s about the moral bankruptcy of commodifying life.

Jesse Ibarra

January 16, 2026 AT 14:34you people are so naive. this isn’t an accident-it’s deliberate. the pharma oligarchs want you dependent, scared, and paying more. they let shortages happen so they can jack up prices on the ‘alternatives’ they own. wake the f up.

sam abas

January 17, 2026 AT 19:13so like… if we just paid more for generics, everything would be fine? lol. what about the fact that 80% of api comes from china? you think we can just ‘make it here’? we don’t even have the labs anymore. also typo: its not ‘sterile’ its ‘sterile’.

Gregory Parschauer

January 19, 2026 AT 11:38let me be clear: this is not a supply chain failure. it is a moral failure. we have allowed the profit motive to override human survival. when a diabetic can’t get metformin because a shareholder demanded a 3% QoQ increase, we are not a society-we are a slaughterhouse with a pharmacy.

the FDA’s task force? laughable. they’re the same people who approved 350 manufacturing violations last year. they’re not fixing the system-they’re polishing the coffin.

and don’t give me that ‘patients should ask their doctors’ crap. my cousin died because the hospital couldn’t get vancomycin. the doctor cried. the hospital sent a thank-you card. that’s the level of care we’ve accepted.

we’ve turned medicine into a spreadsheet. we reward the cheapest bidder, then blame the nurse when the patient codes. we’ve made scarcity a business model and called it ‘efficiency’.

every time you say ‘it’s just a generic,’ you’re signing a death warrant for someone who can’t afford the brand. this isn’t economics. this is eugenics with a pill bottle.

the fact that we’re still debating this instead of nationalizing production speaks volumes. we’d rather watch people suffer than tax a single billionaire.

we need emergency manufacturing hubs. we need guaranteed minimum margins. we need to treat lifesaving drugs like fire extinguishers-not commodities.

until then, we’re not patients. we’re inventory.

Randall Little

January 20, 2026 AT 04:08you know what’s wild? in Japan, they’ve got a national stockpile system and strict supplier contracts. no shortages. no drama. just medicine. we could do that here. but we’d rather argue about whether ‘the market’ is sacred.

Nelly Oruko

January 21, 2026 AT 00:42the real cost isn’t the $213 million hospitals spend managing shortages-it’s the lives lost because someone couldn’t get a $0.10 pill.

Diana Campos Ortiz

January 22, 2026 AT 12:49my dad’s on lisinopril. Last month, the pharmacy said it was ‘temporarily unavailable.’ He waited 11 days. His BP spiked. He ended up in the ER. I called the FDA. No one answered. We need better systems, not just awareness.

laura Drever

January 24, 2026 AT 08:44so like… who’s to blame? lol. everyone. but mostly the guy who bought the cheapest generic and never asked why it was so cheap.

Adam Vella

January 25, 2026 AT 07:20the economic rationale for generic drug pricing is rooted in the principle of perfect competition, yet the market structure exhibits severe oligopolistic concentration, leading to systemic fragility. the absence of price elasticity in essential pharmaceuticals renders traditional market mechanisms inert, necessitating state intervention to internalize positive externalities associated with therapeutic continuity.

John Pope

January 26, 2026 AT 16:08we’re all just waiting for the moment when someone dies from a shortage and the news says ‘this was preventable’-and then nothing changes. we’ve normalized this. we scroll past it. we click ‘like’ and move on. we’re not victims-we’re accomplices.

the real drug shortage isn’t vancomycin or insulin-it’s empathy. we’ve run out of that too.