FDA Orange Book: How to Find Patent Expiration Dates for Generic Drug Access

When a brand-name drug’s patent runs out, generic versions can enter the market. But figuring out when that happens isn’t always simple. The FDA Orange Book is the official source for this information - and if you’re trying to plan when a generic might become available, you need to know exactly where to look and what to watch for.

What the FDA Orange Book Actually Is

The FDA Orange Book, officially called Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations, is not just a list of drugs. It’s a legal record of patents and exclusivity periods tied to each approved small-molecule drug in the U.S. It started as a printed book in 1985 but moved online in 2008. Today, it’s updated daily and used by generic drug makers, pharmacists, and even patients who want to know when a cheaper version of their medicine might show up.It doesn’t list every patent ever filed. Only those that the brand-name company says could be used to block a generic. Each patent listed must be connected to the drug’s active ingredient, formulation, or specific medical use. The FDA requires these to be submitted within 30 days of a patent being issued after the drug’s approval.

Where to Find Patent Expiration Dates

The easiest way to find a patent expiration date is through the Electronic Orange Book. Here’s how to do it step by step:- Go to the Electronic Orange Book website.

- Search by the drug’s brand name (like "Brilinta"), active ingredient (like "ticagrelor"), or application number.

- Click on the drug’s listing - you’ll see a list of approved products.

- Find the product you want and click the hyperlinked Application Number (like "ANDA204567").

- On the next page, scroll down and click "View" under the "Patents" section.

That page shows every patent tied to that drug, with each one listing the patent number, expiration date, and a use code (like "U-889"). The expiration date is shown in the format MMM DD, YYYY - for example, July 9, 2021.

If you’re doing research or need to analyze many drugs at once, the FDA also offers downloadable data files updated every day. These CSV or text files include columns for patent number, expiration date, whether it covers the active ingredient, and whether the patent owner requested to remove it from the list.

What the Expiration Date Really Means

The date you see isn’t just the original patent’s end date. It’s usually extended. The U.S. allows Patent Term Extensions (PTE) under the Hatch-Waxman Act to make up for time lost during FDA review. So if a drug took five years to get approved, the patent can be extended by that amount - up to a maximum of five years, and not beyond 14 years from the drug’s approval date.For example, if a patent was originally set to expire in 2025 but the FDA approval process delayed it by 3 years, the Orange Book will show the expiration as 2028. This is accurate in 93% of cases, according to studies from the National Bureau of Economic Research.

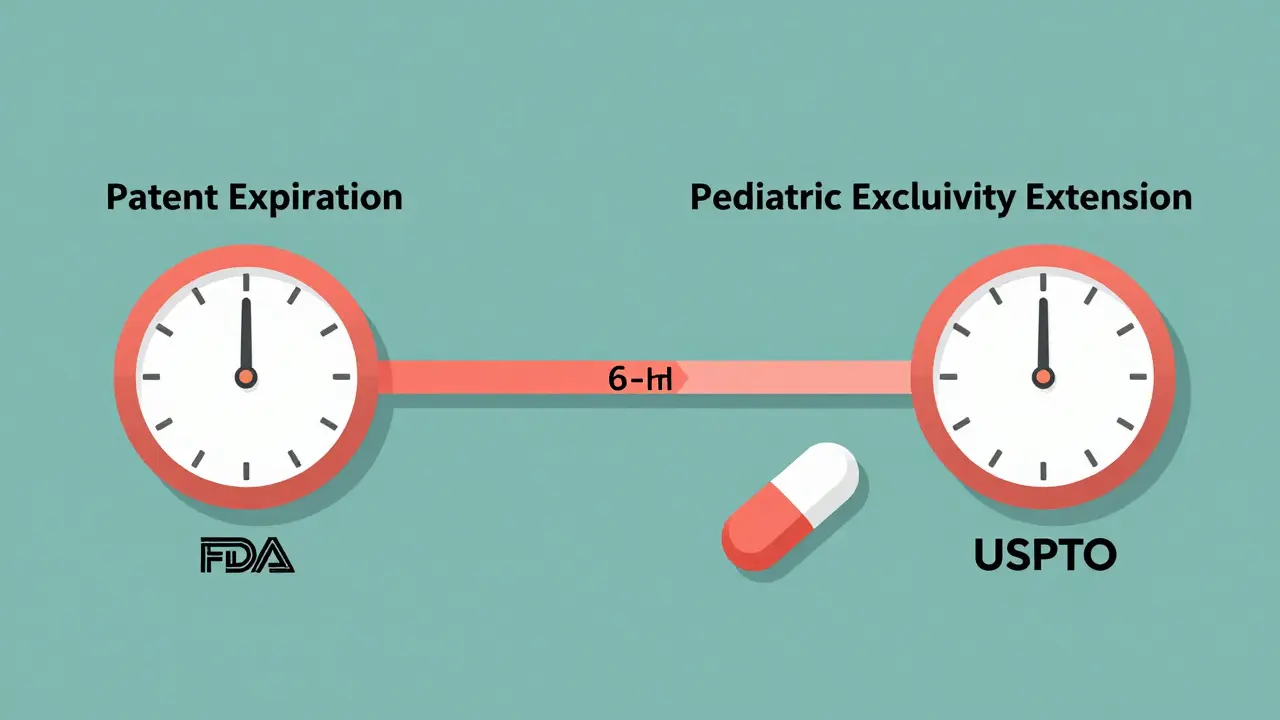

Pediatric Exclusivity: The Hidden 6-Month Extension

Here’s where things get tricky. If a drug maker conducts pediatric studies requested by the FDA, they get an extra 6 months of market protection. This isn’t a new patent - it’s an extension that attaches to every existing patent and exclusivity period for that drug’s active ingredient.In the Orange Book, you’ll see the same patent listed twice: once with the original date and once with the 6-month extension added. This can confuse people who think there are two separate patents. But it’s just one patent with a longer shadow. For example, if a patent expires on January 1, 2026, and pediatric exclusivity applies, you’ll also see a second entry: January 1, 2026 - and then July 1, 2026.

Don’t Trust the Orange Book Alone

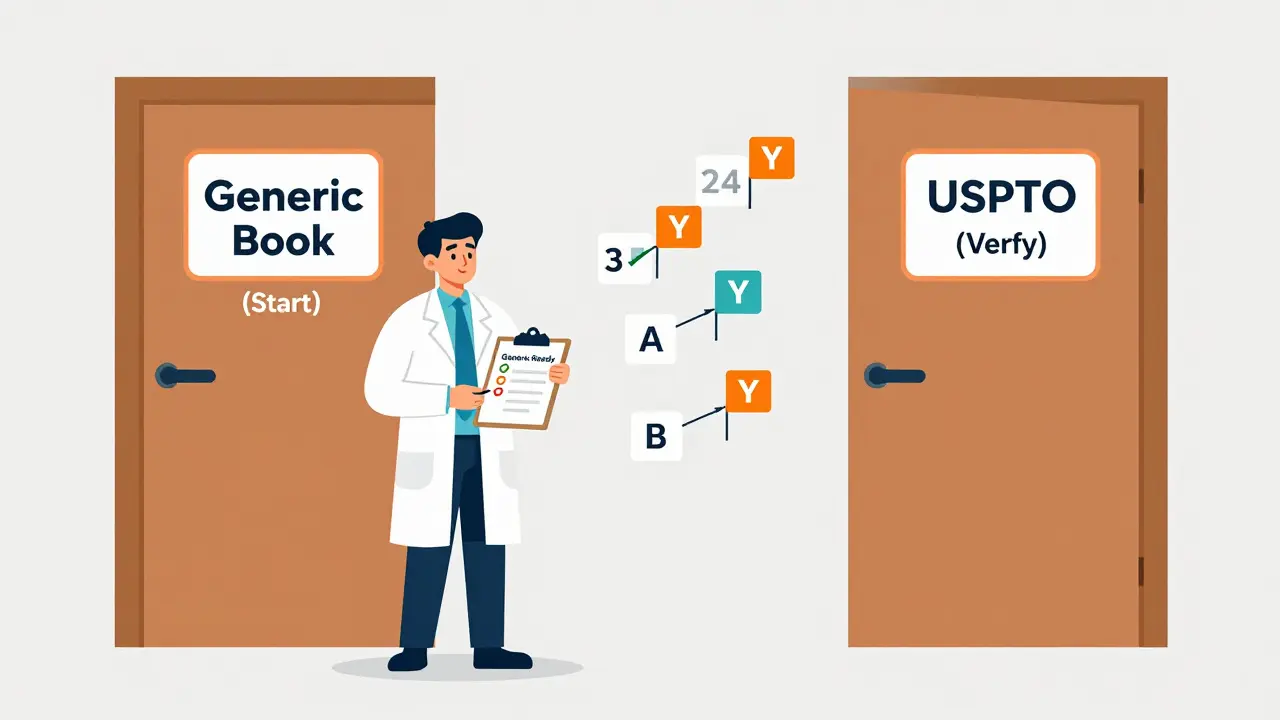

The Orange Book is the starting point - not the final word. A 2023 study found that nearly half (46%) of patents listed in the Orange Book expire earlier than shown. Why? Because patent owners sometimes stop paying maintenance fees. The patent then dies, but the FDA doesn’t go back and update old entries. The patent disappears from public records, but the Orange Book might still list it as active.Also, some patents get delisted voluntarily. If a company requests to remove a patent from the Orange Book, it often means they no longer believe it’s enforceable - maybe it was challenged in court or found invalid. You’ll see a "Y" in the "Patent Delist Request Flag" column. That’s a red flag: the patent might be dead even if the expiration date hasn’t passed.

For accurate planning, always cross-check with the USPTO Patent Center. The FDA doesn’t track whether a patent is still active - only whether it was submitted. The USPTO does.

Exclusivity vs. Patents: Two Different Clocks

Don’t confuse patent expiration with exclusivity. They’re not the same thing. Patents are about invention. Exclusivity is about regulatory approval.For example, a new drug might get 5 years of exclusivity just for being new. Or 3 years if it’s a new use for an old drug. These periods can run separately from patents - and sometimes they’re longer. A drug might have no patents left, but still be protected by exclusivity. That means no generics can enter until that clock runs out.

The Orange Book lists exclusivity dates right next to patent dates. Look for the "Exclusivity Expiration Date" column. If you see one, that’s the real barrier - even if the patent expired years ago.

Why This Matters for Patients and Providers

For pharmacists, knowing when a generic will be available helps with cost-saving substitutions. For patients, it means lower prices. For doctors, it helps when discussing treatment options.And for generic drug makers? The Orange Book is their roadmap. They use it to time their applications. A single patent expiration date can mean millions in revenue - or billions, if multiple drugs open up at once.

By 2025, about 78% of brand-name drug sales will face generic competition. That’s why accurate, up-to-date patent info isn’t just helpful - it’s essential for the entire system to work.

What to Do If You Can’t Find the Date

If you search the Orange Book and don’t see any patents listed for a drug, that doesn’t mean there are none. It could mean:- The patent expired and was removed (FDA deletes expired patents automatically).

- The patent covers something the FDA doesn’t allow to be listed (like a manufacturing process).

- The drug is protected only by exclusivity, not patents.

- The patent was filed before 2013 - and the submission date isn’t tracked.

In those cases, check the drug’s approval history on the FDA’s Drugs@FDA database. It shows when the drug was approved and what exclusivity it received. Combine that with USPTO records, and you’ve got the full picture.

Is the FDA Orange Book free to use?

Yes. The Electronic Orange Book and all downloadable data files are completely free and publicly accessible through the FDA’s website. No registration or payment is required.

Can I trust the expiration dates in the Orange Book?

Mostly, but not always. The dates are accurate for Patent Term Extensions in 93% of cases. However, 46% of patents expire early due to missed maintenance fees, and the FDA doesn’t update those records retroactively. Always verify with the USPTO Patent Center for critical decisions.

Why are there two expiration dates for the same patent?

That’s pediatric exclusivity. When a drug maker completes FDA-requested pediatric studies, they get a 6-month extension on all existing patents and exclusivities. The Orange Book shows the original date and the extended date as two separate lines - it’s not two patents, just one with a longer protection period.

Do biologics show up in the Orange Book?

No. The Orange Book only covers small-molecule drugs - the kind you take as pills or injections that are chemically synthesized. Biologics, like insulin or monoclonal antibodies, are listed in a separate database called the Purple Book.

What does a "Patent Delist Request Flag: Y" mean?

It means the patent owner asked the FDA to remove the patent from the Orange Book. This often happens when the patent is no longer considered enforceable - maybe it was invalidated in court, or the company decided it’s not worth defending. It’s a strong signal that a generic could enter sooner than the listed expiration date.

Next Steps for Accurate Research

If you’re using this info for professional or personal decisions, here’s what to do:- Start with the Electronic Orange Book to get the official expiration date.

- Check the USPTO Patent Center to confirm the patent is still active and hasn’t lapsed.

- Look for any "Delist Requested: Y" flags - those are early warning signs.

- Find the exclusivity expiration date - it might be the real barrier, not the patent.

- If you’re planning a generic launch, monitor the Orange Book weekly. Companies sometimes add or remove patents suddenly.

Patent timelines are the backbone of generic drug access. Getting them right saves money, improves access, and keeps the system fair. The Orange Book gives you the map - but you still need to check the terrain before you move forward.