Dialysis Access: Fistulas, Grafts, and Catheter Care Explained

What Is Dialysis Access and Why Does It Matter?

If you’re on hemodialysis, your access point isn’t just a tube or a needle site-it’s your lifeline. Every time you sit down for treatment, your blood flows out through this access, gets cleaned by the dialysis machine, and flows back in. There are three main types: arteriovenous (AV) fistulas, AV grafts, and central venous catheters. Each has its own pros, cons, and care rules. The goal? To pick the one that lasts longest, causes the fewest problems, and lets you live as normally as possible.

Doctors and guidelines agree: an AV fistula is the best option. It’s made by surgically connecting an artery directly to a vein, usually in your arm. This lets the vein grow bigger and stronger over time so it can handle the needles used during dialysis. Fistulas last for decades when cared for properly. They’re less likely to get infected or clog up. But here’s the catch-they take 6 to 8 weeks to mature before they can be used. That means if you need dialysis right away, you’ll need a temporary solution.

AV Fistula: The Gold Standard

Think of an AV fistula as your body’s own upgrade. No synthetic material. No foreign tubes. Just your artery and vein, joined together. Surgeons typically place it in your non-dominant arm-left if you’re right-handed, right if you’re left. The procedure is outpatient, and recovery is quick. But patience is key.

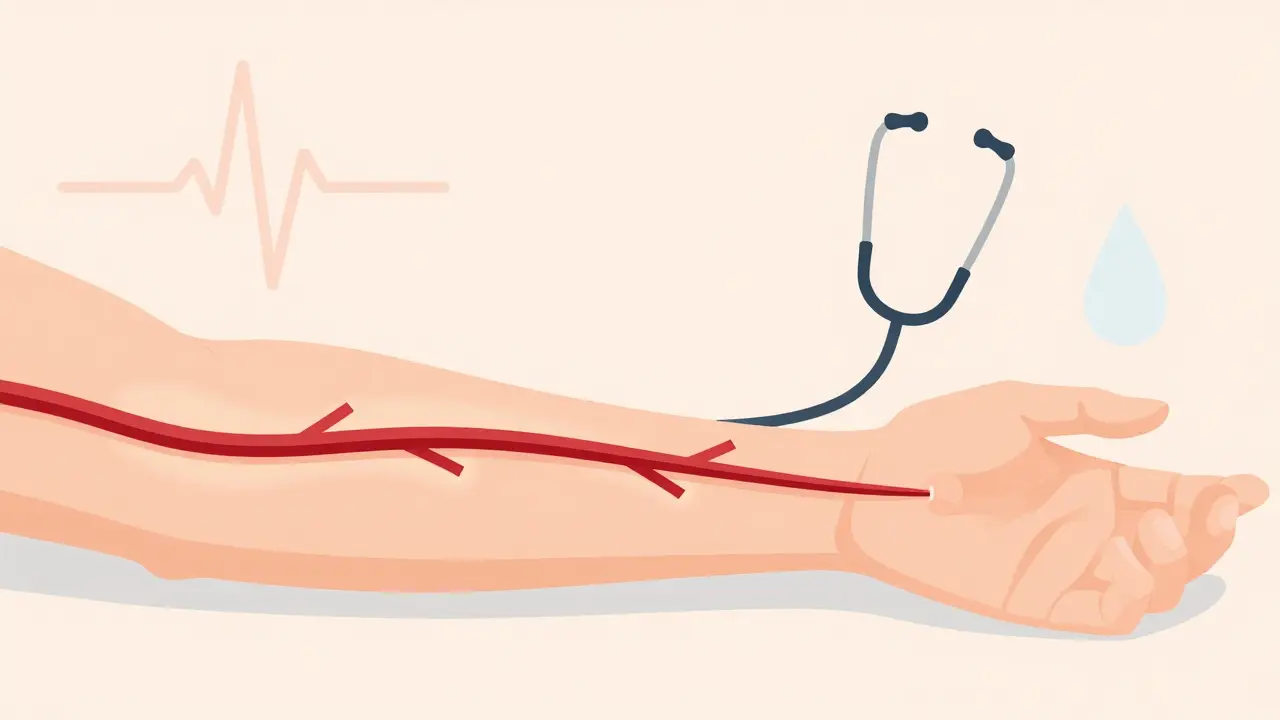

During those 6 to 8 weeks, your vein swells, thickens, and becomes more visible. That’s called maturation. You’ll feel a vibration or buzz under your skin-that’s the thrill. It means blood is flowing properly. If you stop feeling it, call your care team. It could mean a clot is forming.

Once mature, you’ll need to check it daily. Look for redness, swelling, or warmth. Feel for the thrill. Listen for a whooshing sound with a stethoscope (your nurse can teach you how). Wash your arm before every dialysis session. Never let anyone take your blood pressure or draw blood from that arm. Even a tight cuff can damage the fistula.

Studies show fistulas have the lowest infection and death rates. People using them have 36% fewer fatal complications than those with grafts, and more than 50% fewer than those with catheters. One patient in Seattle has had the same fistula for 12 years. That’s the kind of longevity you’re aiming for.

AV Grafts: The Backup Plan

Not everyone has veins strong enough for a fistula. That’s where grafts come in. These are synthetic tubes-usually made of a soft plastic called PTFE-that connect an artery to a vein. They’re used when your natural veins are too small or damaged from diabetes, high blood pressure, or previous surgeries.

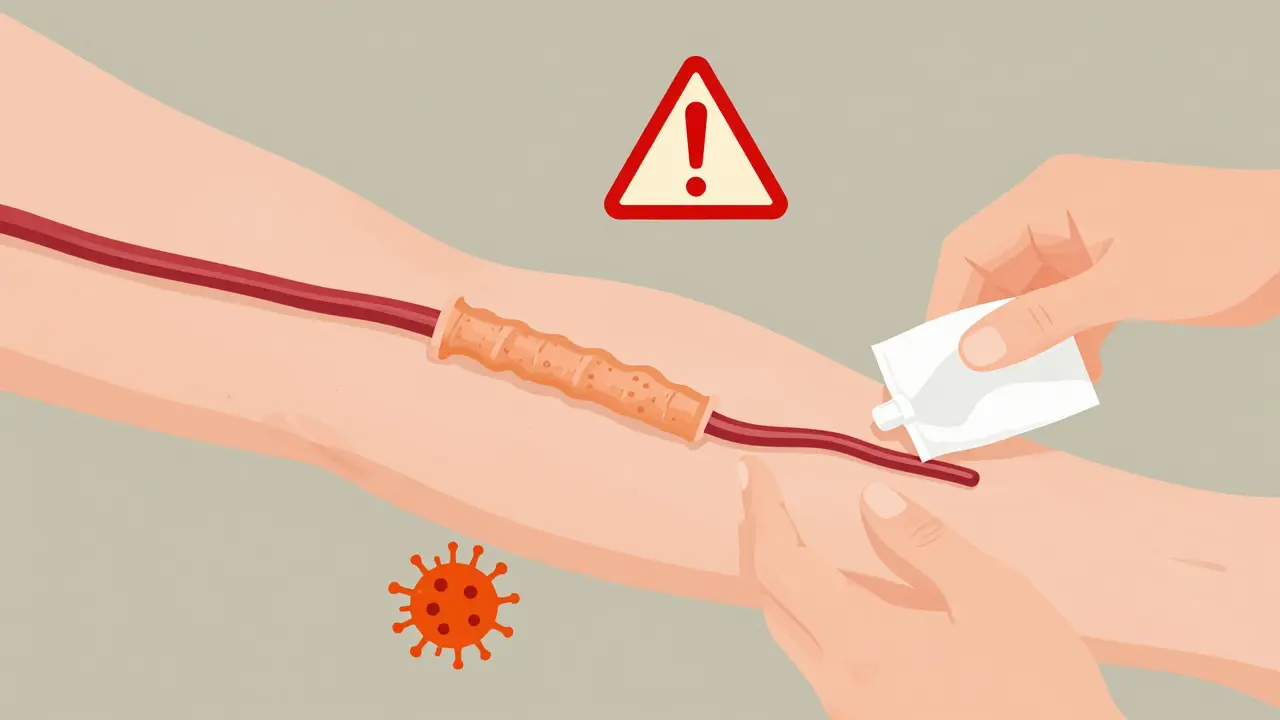

The big advantage? Grafts are ready to use in just 2 to 3 weeks. That’s faster than a fistula. But they come with trade-offs. Grafts are more likely to clot. About 30% to 50% of them need some kind of intervention within the first year. That might mean a catheter to clear the blockage or a minor procedure to widen the graft.

They’re also more prone to infection. Because they’re foreign material, bacteria can stick to them more easily. You’ll need to clean the site carefully before every dialysis session. Watch for redness, pus, or fever. If you notice any of these, don’t wait-call your clinic immediately.

Most grafts last 2 to 3 years before they need replacing. That means you’ll likely go through more procedures than someone with a fistula. But if your veins can’t support a fistula, a graft is still a solid, reliable option. Many patients live well for years with one.

Central Venous Catheters: Temporary, But Sometimes Permanent

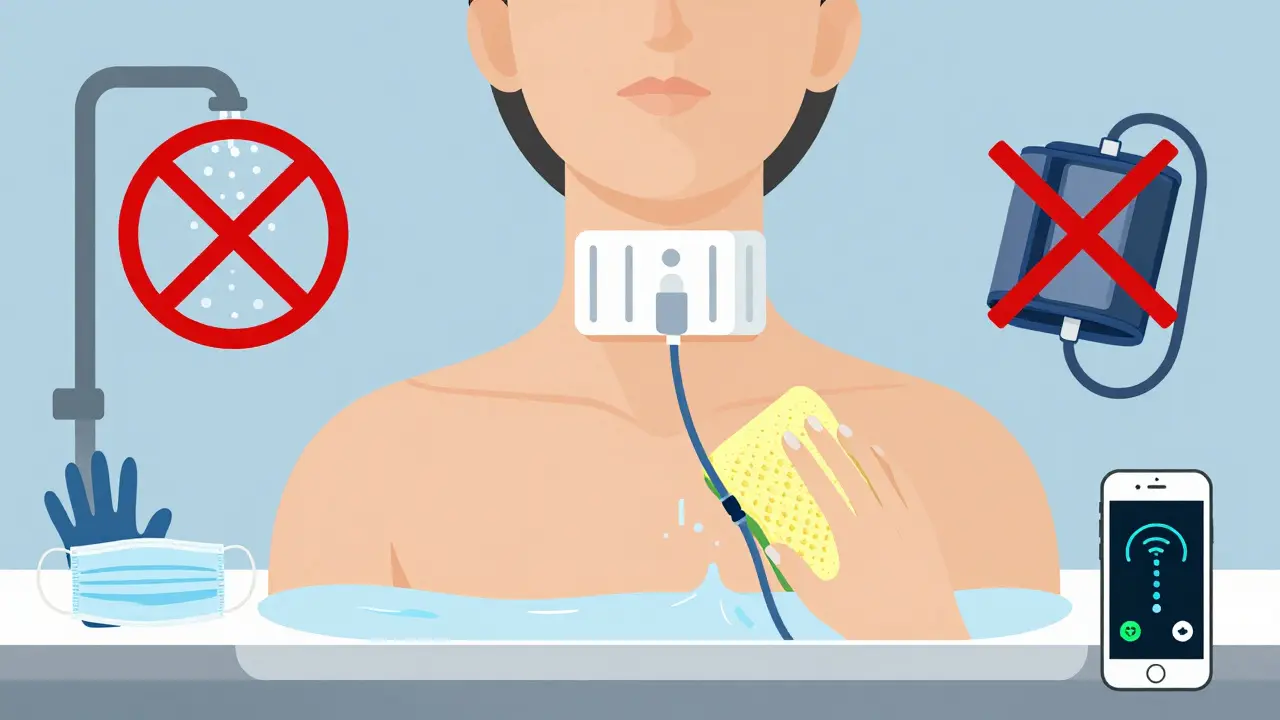

Catheters are soft tubes inserted into a large vein in your neck, chest, or groin. They’re the only access type that works right away. That’s why they’re used for emergencies or while you wait for a fistula or graft to heal.

But here’s the hard truth: catheters are the riskiest option. They’re linked to higher death rates. People using catheters have more than twice the risk of fatal infections compared to those with fistulas. Bloodstream infections from catheters are common, happening at a rate of 0.6 to 1.0 per 1,000 catheter days. That’s why the National Kidney Foundation calls them a last resort.

Keeping a catheter clean is a full-time job. You can’t shower normally-you have to wrap the site in plastic. You can’t swim. You can’t let anyone touch the catheter unless they’re wearing gloves and a mask. Dressings must be changed regularly, and the caps on the ends need to be cleaned with alcohol every single time you use them.

Some patients end up using catheters long-term because they can’t get a fistula or graft. But if you’re in this situation, talk to your care team about options. Are your veins being mapped? Could exercise help? Is there a specialist who can try a more complex fistula? Don’t accept long-term catheter use without asking if there’s another way.

How to Care for Your Dialysis Access Every Day

Regardless of your access type, daily care is non-negotiable. Here’s what you need to do:

- Check for thrill or bruit: Feel your fistula or graft every day. It should buzz or hum. If it stops, it might be blocked.

- Keep it clean: Wash your access arm with soap and water before every dialysis session. Don’t use lotions or creams on the site.

- Don’t sleep on it: Avoid putting pressure on your access arm. Don’t wear tight sleeves or jewelry on that side.

- No blood pressure or blood draws: Never let anyone take blood pressure or draw blood from your access arm. Even once can cause damage.

- Watch for signs of infection: Redness, swelling, warmth, pus, or fever are red flags. Call your clinic immediately.

- Stay hydrated: Good blood flow helps keep your access open. Drink water unless your doctor says otherwise.

Patients who get trained on access care before starting dialysis have 25% fewer complications in their first year. That training isn’t optional-it’s essential. Ask your nurse for a refresher every few months.

Why Some People Can’t Get a Fistula

It’s not just about preference. Many people can’t get a fistula because their veins are too small, too scarred, or too weak. Diabetes, high blood pressure, and aging all take a toll on blood vessels. That’s why vein mapping is so important.

Vein mapping is a simple ultrasound test that shows your doctor which veins are strong enough for a fistula. It’s done before any surgery. If the mapping shows poor vein quality, you might be a candidate for a graft instead.

But here’s something many don’t know: preoperative exercise can help. A 2022 study found that patients who did hand squeezes and wrist curls for 4 to 6 weeks before surgery had a 15% to 20% higher chance of their fistula maturing. It’s not magic-it’s just increasing blood flow to prepare your veins.

Black patients are 30% less likely to get fistulas than white patients, even when they’re medically eligible. That’s a gap that needs to be addressed. If you’re a patient of color, make sure you’re being offered the same options. Ask for vein mapping. Ask about exercise. Ask if a fistula is possible.

New Tech and What’s Coming Next

The dialysis world is changing. In 2022, the FDA approved the first wireless sensor for fistulas-Manan Medical’s Vasc-Alert. It monitors blood flow and sends alerts to your phone if it detects a drop. In clinical trials, it cut clotting events by 20%. That’s huge.

There’s also new graft material in development. Humacyte’s human-made blood vessel, made from donor cells and stripped of immune-triggering parts, is in late-stage trials. It could be a game-changer for people with no good veins.

And the goal? To get fistulas to 70% of all permanent dialysis access by 2030. Right now, it’s around 65%. That means fewer catheters, fewer infections, fewer hospital visits, and more years lived well.

What You Can Do Today

Start with one step: ask your care team if you’re a candidate for a fistula. If you already have a graft or catheter, ask if there’s a chance to switch. Don’t wait until something goes wrong. Prevention is everything.

Learn your access. Feel for the thrill. Wash your arm. Protect it like it’s your most valuable possession-because it is.

What’s the difference between a fistula and a graft?

A fistula is made by connecting your own artery and vein together. It’s your body’s natural tissue and lasts longer with fewer complications. A graft uses a synthetic tube to connect the artery and vein. It works faster but is more prone to clots and infections. Fistulas are preferred; grafts are used when veins aren’t strong enough.

How long does it take for a fistula to be ready?

It takes 6 to 8 weeks for a fistula to mature. During that time, your vein grows larger and stronger to handle the needles used in dialysis. You’ll feel a vibration-called a thrill-when it’s ready. If you don’t feel it after 8 weeks, talk to your doctor.

Can I shower with a catheter?

You can, but only if you protect the catheter site completely. Use waterproof covers or plastic wrap to keep it dry. Never let the catheter get wet, as moisture increases infection risk. Many patients find it easier to use a sponge bath until they get a fistula or graft.

Why is my fistula not working?

If your fistula isn’t buzzing or feels hard, it might be blocked by a clot. Other causes include low blood flow, scarring, or poor vein health. Call your dialysis center right away. They can do an ultrasound or a procedure to clear it. Early action can save your access.

Are there exercises I can do to help my fistula?

Yes. Simple hand squeezes with a soft ball or stress ball, 10 times an hour while awake, can help increase blood flow to your arm. Studies show this can improve fistula maturation by 15% to 20%. Start 4 to 6 weeks before surgery if possible, and keep doing it after.

What should I do if my access gets infected?

Call your dialysis center or doctor immediately. Signs of infection include redness, swelling, warmth, pus, fever, or chills. Do not wait. Infections from catheters can spread fast and become life-threatening. For fistulas and grafts, infection is rare but serious. Treatment usually involves antibiotics and sometimes surgery.

What Comes Next?

If you’re on dialysis, your access is your most important health tool. It’s not just about surviving treatments-it’s about living well between them. Talk to your care team about your access type. Ask if you’re eligible for a fistula. Learn how to check it daily. Advocate for yourself. And if you’re helping someone else, make sure they know: this isn’t just medical advice. It’s life-saving routine.

Frank Declemij

January 29, 2026 AT 07:17Been on dialysis 8 years. Same fistula. No infections. No surgeries. Just discipline.

Pawan Kumar

January 29, 2026 AT 20:36Keith Oliver

January 31, 2026 AT 10:00Kacey Yates

February 1, 2026 AT 08:58ryan Sifontes

February 2, 2026 AT 01:27Laura Arnal

February 2, 2026 AT 08:18Jasneet Minhas

February 3, 2026 AT 08:40Eli In

February 4, 2026 AT 10:51Megan Brooks

February 5, 2026 AT 23:53Ryan Pagan

February 6, 2026 AT 18:41Paul Adler

February 7, 2026 AT 11:51Sheryl Dhlamini

February 8, 2026 AT 19:00Doug Gray

February 9, 2026 AT 09:49Kristie Horst

February 11, 2026 AT 08:05