Antitrust Laws and Competition Issues in Generic Pharmaceutical Markets

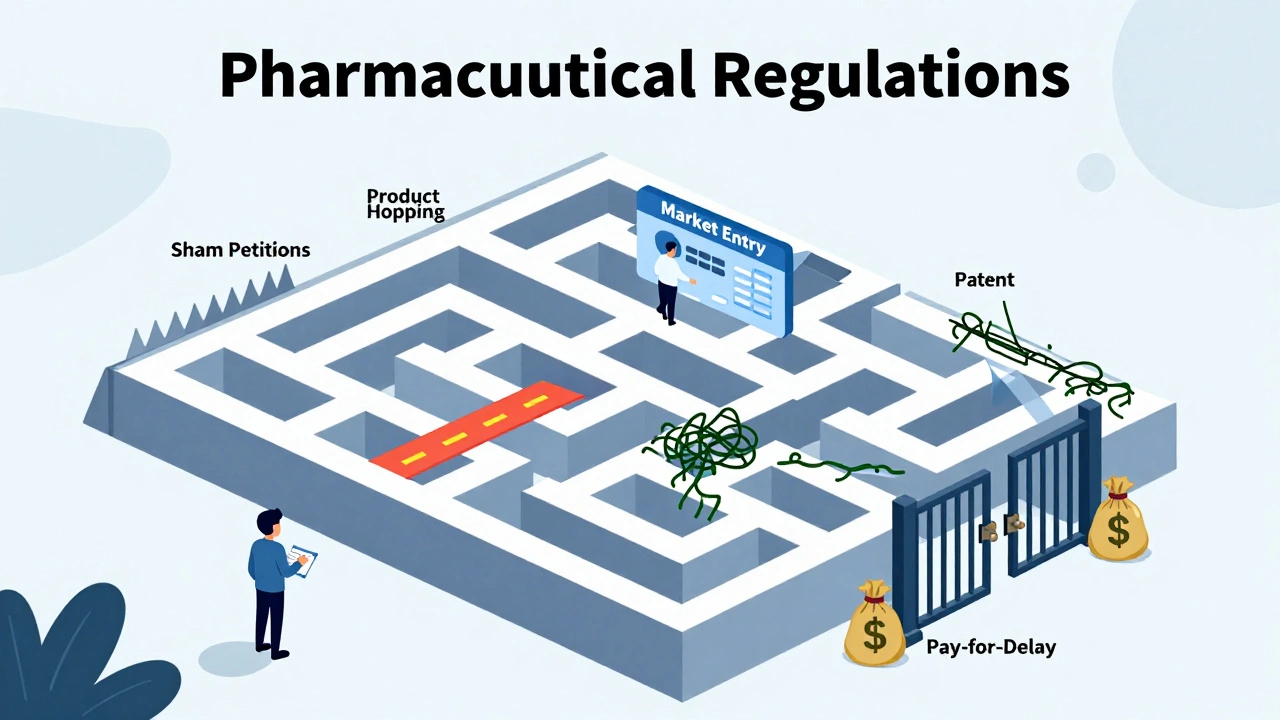

When you walk into a pharmacy and pick up a generic version of your prescription, you’re benefiting from a decades-old legal battle over competition, patents, and fair pricing. But behind that cheap bottle of pills lies a complex web of rules, lawsuits, and corporate tactics designed to keep prices high - even after a drug’s patent expires. Antitrust laws are meant to stop this, but in the generic drug market, they’re often stretched thin, exploited, or ignored entirely.

How the Hatch-Waxman Act Was Supposed to Work

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act - better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. Its goal was simple: let generic drug makers enter the market faster without forcing branded companies to give up their innovation incentives. The law created a shortcut for generics: instead of running full clinical trials, they could prove their drug was bioequivalent to the brand-name version. All they had to do was file an Abbreviated New Drug Application, or ANDA. The real game-changer? The first generic company to challenge a patent with a Paragraph IV certification got 180 days of exclusive market access. That meant they could be the only generic on the shelf, selling at a steep discount to the brand, while still making a profit. This was supposed to spark a race to the bottom - and it did. By 2016, generic drugs accounted for 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., up from just 19% in 1984. Between 2005 and 2014, Americans saved $1.68 trillion because of generics. In 2012 alone, the savings hit $217 billion. But the system wasn’t built to handle what came next.Pay-for-Delay: The Secret Deal That Kills Competition

Instead of racing to be first, some branded drug companies started paying generic makers to stay away. These deals, called “pay-for-delay” agreements, are exactly what they sound like: the brand pays the generic to delay launching its cheaper version. In exchange, the generic gets a cut of the brand’s profits - sometimes hundreds of millions of dollars. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has called these agreements “the most egregious form of anticompetitive behavior” in the pharmaceutical industry. In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in FTC v. Actavis that these deals could violate antitrust law if they involve large, unexplained payments. But proving it is hard. Courts still allow some settlements if they claim there’s a “legitimate” reason - like sharing patent litigation costs. One of the biggest cases involved Gilead Sciences. In 2023, the company paid $246.8 million to settle allegations it paid generic makers to delay the launch of a cheaper HIV drug. The settlement didn’t admit wrongdoing, but it was a clear signal: regulators are watching.Product Hopping and Patent Games

Another tactic? Product hopping. This is when a brand-name company makes a tiny, meaningless change to its drug - like switching from a pill to a capsule, or adding a new coating - right before the patent expires. Then they market the new version as “improved,” even though it offers no real benefit. Patients are nudged to switch, and pharmacies follow suit. The old version gets pulled from shelves, and the generic version can’t launch because there’s no original drug left to copy. AstraZeneca did this with Prilosec and Nexium. Prilosec’s patent was about to expire. So they launched Nexium - a slightly modified version - and convinced doctors and patients it was better. Within months, Prilosec disappeared from pharmacies. Generic Prilosec couldn’t enter because there was no branded version left to reference. The FTC called it a “classic” anticompetitive move. Courts didn’t always agree - in one case, they dismissed the claim because AstraZeneca never blocked generic entry outright. But the effect was the same: consumers paid more for longer.

Sham Petitions and Orange Book Abuse

Then there are sham citizen petitions. Anybody can file one with the FDA, asking them to delay approval of a generic drug over safety or efficacy concerns. Legitimate petitions? Rare. Most are filed by branded companies pretending to care about patient safety - when they’re really just trying to stall. Teva Pharmaceuticals is currently under FTC investigation for allegedly filing dozens of these petitions to delay generic versions of its multiple sclerosis drug, Copaxone. The agency says the claims in these petitions were baseless and repeated, and that Teva used them as a delay tactic. The case is still pending. The Orange Book - the FDA’s official list of approved drugs and their patents - is another tool for abuse. Brand companies sometimes list patents that don’t even cover the drug’s active ingredient. They list method-of-use patents, delivery system patents, or even expired patents. That blocks generics from entering because the FDA won’t approve them until all listed patents are resolved. In 2003, the FTC went after Bristol-Myers Squibb for listing patents that didn’t apply to the drug’s formulation. The goal? To extend monopoly control. The company settled, but the practice continues.Global Differences: What Other Countries Are Doing

The U.S. isn’t the only place fighting this battle - but its approach is unique. In the European Union, regulators focus on how companies manipulate regulatory processes to block generics. That includes withdrawing marketing authorizations in specific countries to prevent parallel imports or filing misleading patent applications to extend protection. The European Commission estimates that delays in generic entry cost European consumers €11.9 billion every year. Between 2018 and 2022, 60% of their 27 pharmaceutical antitrust cases dealt with blocking generic competition. China took a harder line in January 2025, releasing new Antitrust Guidelines for the Pharmaceutical Sector. They identified five “hardcore restrictions” that are automatically illegal: price fixing, output limits, market division, joint boycotts, and blocking new technology. By Q1 2025, they’d already penalized six cases - five of them involved price fixing through text messages, apps, and even algorithms. China is also using AI to monitor drug prices in real time. If a group of generic makers suddenly raise prices together, the system flags it. No more hiding behind “market conditions.”

pallavi khushwani

December 7, 2025 AT 08:27It's wild how a law meant to help people ended up being a playground for lawyers and CEOs. I remember my grandma skipping her blood pressure meds because the generic was still too pricey - and she wasn't even the one getting gouged. The real villain isn't the system, it's the silence around it. Everyone just shrugs and says 'that's just how it is.' But it doesn't have to be.

Billy Schimmel

December 8, 2025 AT 07:48So let me get this straight - we pay billions so drug companies can pay other drug companies to not sell cheaper stuff? And we call this capitalism? Wow. I'm glad I don't have a heart condition.

Max Manoles

December 10, 2025 AT 05:03The Hatch-Waxman Act was a triumph of legislative engineering - until corporate incentives warped its architecture. The 180-day exclusivity window was never designed to be a bargaining chip for collusion. When patent litigation becomes a profit center rather than a legal safeguard, the entire premise of market competition collapses. The FTC’s reactive enforcement is akin to mopping the floor while the faucet is still running.

Katie O'Connell

December 11, 2025 AT 16:39One cannot help but observe the tragicomic dissonance between the ostensible objectives of public health policy and the actual machinations of market actors. The institutional capture of regulatory mechanisms - particularly the Orange Book and citizen petition processes - constitutes a systemic failure of fiduciary responsibility. One must ask: is this not the very definition of rent-seeking in its most pernicious form?

Annie Gardiner

December 12, 2025 AT 03:36Wait, so you're saying the government created a system to lower drug prices… and then drug companies figured out how to use it to make MORE money? That’s not a loophole - that’s just how America works. Maybe we should just let the rich buy all the medicine and the rest of us learn to breathe slower.

Kumar Shubhranshu

December 13, 2025 AT 13:53China uses AI to catch price fixing. We still argue if pay-for-delay is illegal. The gap isn't policy. It's will.

Kenny Pakade

December 14, 2025 AT 09:48Why are we even talking about this? The U.S. leads the world in innovation. If you can't afford your meds, maybe you shouldn't be on them. China's system is socialist nonsense. We don't need AI watching pharmacies - we need less regulation and more American grit.

brenda olvera

December 14, 2025 AT 19:31My cousin in India gets her insulin for $3 a month. Here it's $300. We have the tech. We have the money. We just don't have the heart. Maybe we need to remember we're all human first.

olive ashley

December 16, 2025 AT 15:59Did you know the FDA is secretly owned by Big Pharma? They don’t just delay generics - they bury them. The Orange Book? A scam. The FTC? A front. The real reason you can’t get cheap meds is because the government wants you sick. It’s the only way they control the population. You think this is about profit? No. It’s about control.